Born Within These Walls: The Lying-In Hospital

By Kate Reggev

Over the past year, In Ink has largely focused on telling the stories and history of early female architects and the spaces they designed. But just as important (and, in fact, significantly more common!) are the spaces that were typically designed and built by men — but specifically for women. From waiting rooms to delivery rooms, these spaces followed the views of where and how men believed women should inhabit (and wait, deliver, and simply just be in) the world.

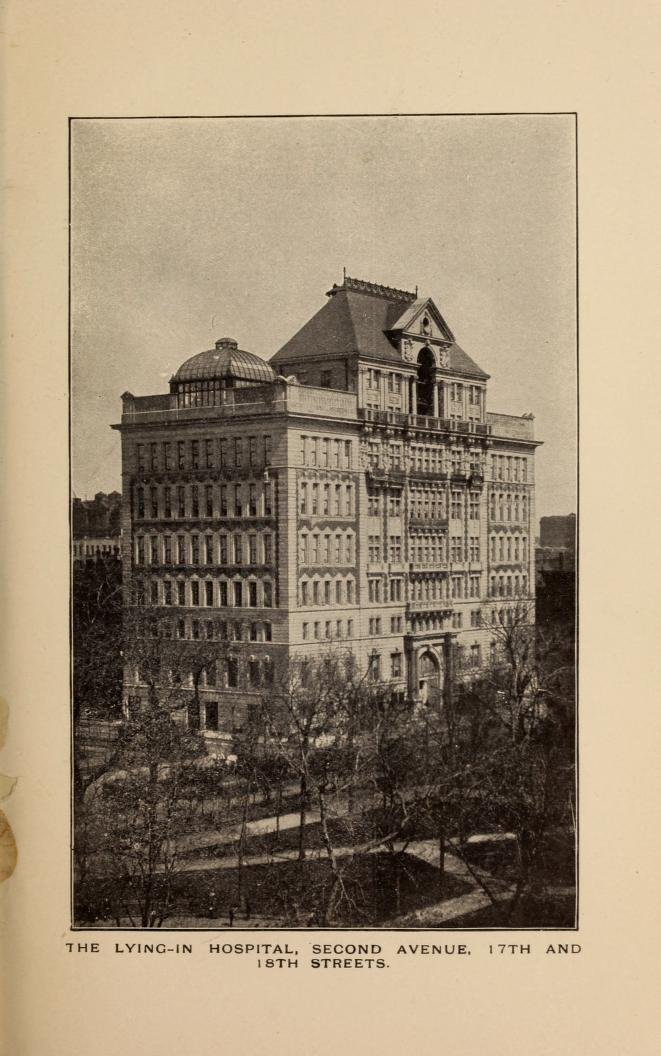

The Society of the Lying-in Hospital of the City of New York, 1899. Rendering of Exterior from the Annual Report.

And while some of these spaces seem fun and even amusingly antiquated to our modern sensibilities (do we really need separate entrances into schools? Our own waiting rooms in train stations? A room to powder our noses before going into a restroom at a department store?), others still very much still exist, albeit under other guises or nomenclature. One such space was the lying-in hospital, a medical facility which was typically established in major cities in the mid- to late-nineteenth century all over the world, from Boston to San Francisco, Italy to India.

Of course, you might wonder, who (or what) were the lying-in? And where were they “lying”? The comically euphemistic term refers not to spaces where someone might spend their days leisurely lying around but rather to the hospitals where women did just about the opposite: where they went through the daunting and often dangerous experience of giving birth. Indeed, the name comes from the European practice of weeks (or months) of bedrest before and after giving birth, with the idea that women needed to remain “lying in” their beds during this period of childbirth.

And although the first known use of the term “lying in” dates back to the 15th century, New York’s first lying-in hospital originated as a charity organization for poor and destitute women in 1799. The Society for the Lying-In, as it was called, had its first location down on Cedar Street in the early 1800s but was taken over by New York Hospital shortly thereafter. By the late 1800s, the Society had merged with the Midwifery Dispensary, a clinic founded by Dr. James Markoe that operated out of a house at No. 312 Broome Street on the Lower East Side. However, the massive influx of immigrants — Markoe’s typical patient — to New York during the late nineteenth century meant that the clinic soon needed to expand.

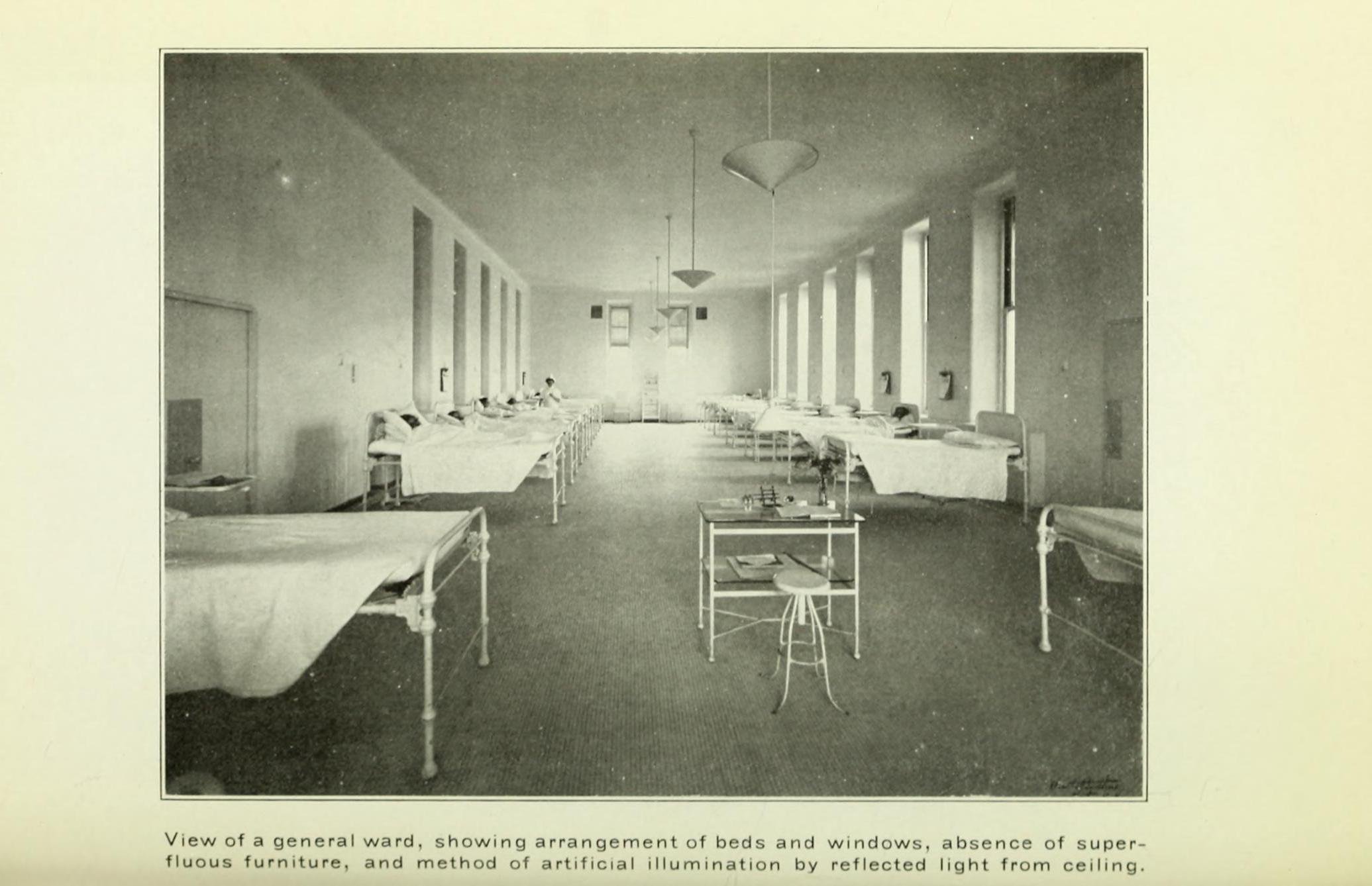

General maternity ward. Courtesy of The Society of the Lying-in Hospital of the City of New York, 1912

The amphitheater, used for operations and demonstrations. Courtesy of The Society of the Lying-in Hospital of the City of New York, 1912

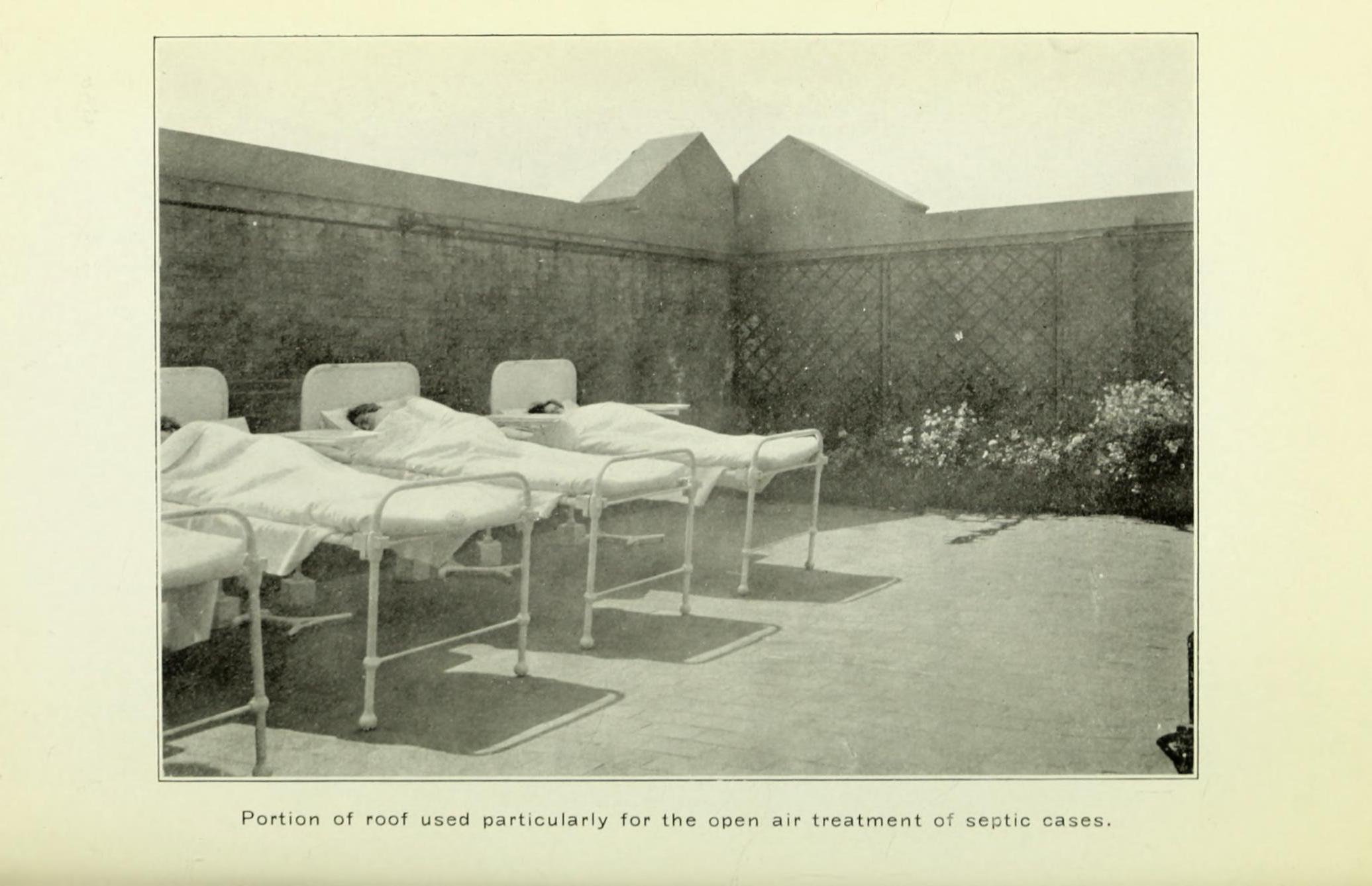

Beds in open air for septic patients, Courtesy of The Society of the Lying-in Hospital of the City of New York, 1912.

Enter millionaire J.P. Morgan, a patient and friend of Dr. Markoe. Morgan donated a large chunk of money to purchase a formerly bucolic residence on Second Avenue and 17th Street and retrofit it as a hospital, where it functioned for a few years as the new clinic. However, by the late 1890s, Morgan hired architect Robert Henderson Robertson (try saying that name three times fast!) to design a new facility on the property. Morgan stipulated that its design needed to meet the approval of Dr. Markoe, who spent six months traveling in Europe to learn the latest architectural solutions to reduce the spread of disease and germs as well as best practices for maternity wards.

Today, it might strike us as surprising, if not even slightly insulting, that neither Morgan, Markoe, nor Robertson appear to have consulted a single woman on the types of spaces they were interested in using or giving birth in. But it’s important to remember that every building is “of its time,” meaning that it’s subject to the whims and prejudices of those who designed it and the ideas that circulated at that moment in time. In the late 1800s, the idea of men funding, researching, designing, and constructing a space that would be used almost exclusively by women was not out of the ordinary; moreover, there were very few women practicing architecture or medicine at the turn of the century, so it would have been quite extraordinary for women to have a say in the matter.

Exterior of the Lying-In Hospital. From the Annual Report - The Society of the Lying-in Hospital of the City of New York, 1906

And, I should mention, just the fact that there were doctors who were interested in obstetrics and designing a cutting-edge maternity ward was itself contentious. Previously, childbirth was seen as almost irrelevant (if not ungentlemanly!) to doctors, who relegated birth and the health of pregnant women to other women, often midwives whose experience might have ranged from minimal and informal to highly skilled and knowledgeable (to be clear — midwives today are well-trained medical professionals!). Indeed, high infection rates at the few maternity wards that existed in the mid-1800s led many to believe that the safest place for a baby to be born was at home. However, a better understanding of germs and their spread around the turn of the 20th century not only changed hospital design but also the idea that hospitals could potentially be safer than home births.

Architect Richard Henderson Richardson. Courtesy Shelburne Farms.

At the time of its completion in 1902, New York’s new Lying-In Hospital was designed to accommodate 250 patients within its seven stories (plus a three-story attic). Scholar Jeanne Kisacky, in her extremely thorough paper on the building, referred to the hospital as “a skyscraper" in contrast to the other low-rise, decentralized facilities typically designed at the time, who had low-lying wards separated from each other by long corridors. The Lying-In Hospital’s facade, constructed of limestone, brick, and terra cotta with a rusticated base, was executed in a Beaux Arts style with Corinthian columns flanking the double-story entry.

And while I may have some mixed feelings about the concept of an all-male cast of characters designing the hospital, I delight in a few small details that are visible upon closer inspection: the facade bears circular reliefs depicting semi-swaddled babies, their chubby tummies sticking out, and portraits in relief of infants’ faces with plump cheeks adorn the double-height arched entryway. I adore moments like this, when the strictness of Classical architecture and Beaux-Arts training slackens their vice-like grip and give way to something that shows personality and, quite literally, life; where we, the public, suddenly understand from the exterior of a building its private, interior use — without the need for floor-to-ceiling windows to show us. Did I mention that these babies are also very cute??

Apparently, though, not everyone felt this way. A letter, now framed in the building’s lobby, lauded Morgan for his “princely gift” but did not appreciate the unclothed children depicted on its facade, asking “Is it necessary to have nude figures of male children only, when both male and female children are treated in the institution?” In all fairness, it’s difficult to tell the gender of the babies on the facade.

The building was also specifically designed to reduce the spread of germs, with interiors outfitted with easy-to-clean materials and details where dirt and dust would not easily accumulate: plaster coated with several layers of enamel paint; coved ceilings and baseboards so that there were no corners; surfaces clad in ceramic tile with narrow grout lines; floors covered in lignolith, a seamless, waterproof flooring made of cement and sawdust; and miles (yes, miles!) of ductwork that isolated various spaces to ensure that cross-contamination did not occur. Even the radiators, located directly below windows, were encased in curved covers, their nooks and crannies hidden from potential dust mites.

First Floor Plan from the Annual Report - The Society of the Lying-in Hospital of the City of New York, 1899.

Over the years, the building, according to the New York Times and a 1984 Bulletin of the American Academy of Medicine, was said to account for 60 percent of all births in Manhattan. In 1934, the Hospital moved uptown to East 70th Street, and the building changed hands in the ensuing decades, at one point still serving as a maternity hospital but updated and outfitted with a beauty parlor, barber shop, soda fountain, cafeteria, lending library, and arrangements for a radio in every room (fancy! And entertaining for long hours of labor). In the 1960s and 1970s, it housed a drug treatment facility until its conversion into a condominium in the 1980s, which retained the original marble-clad lobby and exterior elements (full disclosure: the architecture firm where I work, Beyer Blinder Belle, was responsible for the design of the conversion in 1983, but I had no part in it! I myself was not yet an infant at the time).

The Lying-In Hospital aka 305 Second Avenue entrance. Courtesy of Wikipedia User Beyond My Ken.

So what do we make of all of this? There’s the narrative about men designing spaces for women, to be sure; as educator and activist Leslie Kanes Weisman contends, “the hospitalization of childbirth placed the economic and biological control over women's reproductive capacity exactly where the rising male medical establishment wanted it — with themselves." Another point of consideration is that we are no longer completely obsessed with sterile environments; in fact, today some maternity wards encourage bringing in personal items like pillows, pictures, and the like to bring comfort to patients going through labor. And while some details continue to be important, like rounded corners and impervious surfaces for easy cleaning or extensive ductwork to prevent the spread of disease, color has also entered the maternity ward and spaces are no longer exclusively aseptic white.

But finally, I think there’s also an interesting thread about money, healthcare, and space. It used to be that only the poor gave birth in hospitals because they had nowhere else to go or because their homes could not provide, as doctors believed, the sanitary conditions required for a birth; wealthy or even middle-class women continued to give birth at home but in the presence of a doctor into the 1900s. But the rise of the maternity ward and the promise of a “sterile” environment led to hospitalized care becoming the norm for nearly all women by the 1920s and 1930s. Today, the high costs of giving birth in a hospital and the renewed interest in home births and midwifery is just one of many reminders that history — and life! — is cyclical. What’s old is new, and what was designed and born in 1902 as a maternity hospital is, quite literally, reborn today as a condominium.

More reading?

“The Lying-In Hospital,” The New Yorker, October 19, 1929 P. 80

“Germs are in the details: Aseptic Design and General Contractors at the Lying-In Hospital of the City of New York, 1897-1901” by Jeanne Kisacky

Rise of the Modern Hospital: An Architectural History of Health and Healing, 1870-1940 by Jeanne Kisacky

“The Maternity Hospital: Blueprint for Redesigning Childbirth” by Leslie Kanes Weisman in Motherhood and Space:

Configurations of the Maternal through Politics, Home, and the Body, edited by Sarah HardyCaroline Wiedmer

“A Chance to Return to Your Roots,” by Nadine Brozan in The New York Times, January 22, 2006