A Room Of Her Own: Where Early Female Architects Lived

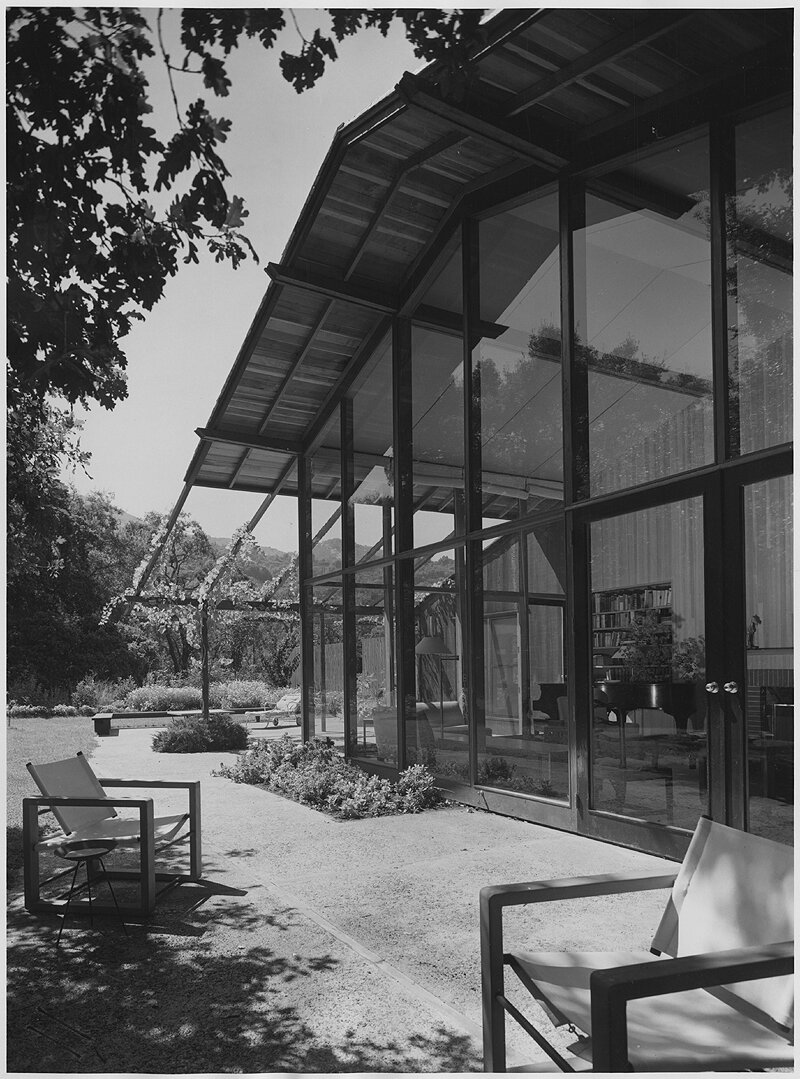

Family residence of architect Rebecca Wood Esherick Watkin, Kentfield, CA. Exterior view. Photograph ca. 1955. “Rebecca Wood Watkin Architectural Drawings, 1940–1989,” Ms1995-009. Courtesy Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Library, Blacksburg, Va

By Kate Reggev

Ah, to be young, single, and earning a wage. Today, we may think that spells out freedom, but the reality for most working women around the turn of the century was far from that, particularly when it came to their living quarters. We recently discussed the many jobs that women in architecture held in the 1920s, ranging from stenographer and bookkeeper in others’ offices to draftswoman and female architect at their own firms; at the same time, we’ve also discussed how those few women who did practice architecture in the decades before and after the turn of the 20th century were believed to be naturally inclined to design residential buildings, since the domestic was, after all, their purported “domain.” But what about their own homes? Did these women typically design the spaces that they themselves inhabited? Where — and how — did these working women actually live, and to what extent did they have free reign over these choices?

For starters, it’s important to understand the context in which women entered the American workforce. Starting in the mid- to late 1800s, unmarried (predominantly white) women began to join the labor force as industrialization took hold (maybe you remember learning about the Lowell textile mills and the Lowell mill girls in high school history class?). While women entering the workforce was undeniably a boon for the economy and national productivity in the United States, for many it presented some serious moral issues and challenged what was seen as the traditional place — both literal and figurative — for women: at home.

Despite these widespread beliefs, women began entering the working world in droves, and by the late 1800s were flocking to industrial centers and major cities. Between 1870 and 1920, women in the workforce increased by more than 60% in jobs that included positions in factories and offices, but also some professionals in education, medicine and the arts — including architecture.

Hotel Martha Washington, New York, 1904. Library of Congress

One of the biggest challenges for these women, though, was determining where to live, because with that “where” were embedded assumptions and implications of class, safety, morality, and more (think: celibacy, purity, and the Victorian ideal of a woman). By the early 1900s, there had already been decades-long discussions about where and how single women should live, whether it was in specially-designed boarding houses with strict moral codes like at Lowell, women-only hotels like the Hotel Martha Washington in New York City with curfews but spaces for male and female visitors, or as a boarder in a shared home or apartment among friends, family, or strangers.

Lobby, Hotel Martha Washington, 1914. Museum of the City of New York

For architects, the matter was particularly personal, given their intimate relationship with space and the built environment, but that did not always spell out the choicest locale, the most elegant of accommodations, or even the ability to personalize a space. Early Black female architect Ethel Bailey Furman (1893-1976), for example, was living in a large apartment building at West 136th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard in Harlem with her husband, two children, extended family, and two lodgers according to the 1920 census. Although she wasn’t single at the time, this was a common living arrangement for working women who couldn’t afford an entire apartment themselves; living with relatives was also considered more socially appropriate than, say, living as a lodger with strangers, many of whom may have been older single men. While taking in lodgers was by no means unusual, it was certainly a sign of being working or lower-middle class, and it’s possible that the Bailey-Furman family needed this extra income because of the higher housing costs that Black residents were subjected to because of their race.

On the other side of the city, architect Anne Grant was living in 1900 as a lodger on East 28th Street near Madison Avenue; at the time, she was working as a draftswoman for famed architect Grosvenor Atterbury, with work acknowledged and published by the architectural press. By 1920, she had moved to the decidedly bohemian, artistic West Village in an apartment with her older sister, a secretary. Ironically, while Anne drew expansive, grand residences in the tri-state area, she, like other female architects of the time, lived in buildings that were virtually always designed by male builders and architects. What’s more, as a renter in these buildings, it is unlikely that she was able to have significant impacts on the spaces she inhabited.

Hill-Stead by Theodate Pope Riddle and McKim, Mead and White. Courtesy of Hill-Stead Museum

On the other hand, wealth and financial stability could be one of the few means for these early female architects to design their own homes. Theodate Pope Riddle (1867-1946), for example, was the well-off daughter of industrialist Alfred Pope and designed Hill-Stead, a grand estate in Farmington, Connecticut for her parents and herself starting in the 1890s. Created in collaboration with staff at McKim, Mead and White, the complex was inspired by Connecticut farmhouses; as early as 1889, she insisted that its design be “a Pope house instead of a McKim, Mead, and White,” and that she would “decide on all the details as well as all the more important questions of plan that may arise.” Not only did Pope Riddle have the satisfaction of living in her own design, but she also continued to contribute to the property’s evolution and long-term planning, designing additional buildings for the property into the 1910s and later deeding it in her will to open as a public house museum upon her death.

As more and more women trickled into architectural studies and practice in the 1920s and 1930s, they slowly started to design their own residences. This was particularly the case for women who married other architects, which enabled them to continue working despite the prevailing expectation at the time that even educated women with careers would stop after marriage. Importantly, though, it also dovetailed with the belief that women were virtually destined to practice residential architecture, and architectural press at the time often noted their knowledge of kitchen layouts and closet size.

Theodate Pope Riddle at Avon Old Farms, Avon, Conn., circa 1925. Hill-Stead Museum.

Early examples of this phenomenon included the home of incredibly successful and prolific architect Verna Cook Salmonsky (1890–1978) and her husband Edgar Salomonsky, who designed their own residence in the then-quickly growing New York suburb of Scarsdale in 1926. Back in New York City, fellow Columbia University graduate Mary Elizabeth Houck Smith-Miller (1909-1996) married classmate and architect Theodore Smith-Miller in 1933, and the two worked together (along with Walter Sanders and John Breck) to design the renovation of their Modernist townhouse in 1939-1940. The facade was described as “honest and ingenious” with its ground floor office, single-floor apartments, and a “handsome facade” with horizontally-run corrugated aluminum siding and 14-foot wide windows.

By the 1940s, academic environments that had previously rebuffed women’s intentions to study architecture were suddenly open and accepting female students to make up for the seats emptied by men serving in World War II, further increasing the number of female architects by midcentury. And as the number of practicing female architects grew, so too did the number of women living in homes that they themselves had designed, in part thanks to the postwar growth of the suburbs and a housing boom.

Soon, husband-and-wife architectural duos were (relatively) frequently designing their own homes, from household names like Charles and Ray Eames (1912-1988), who designed Case Study House No. 8 (today known as the Eames Foundation) as their home and studio in 1949, to more locally-recognized architects like Margaret King Hunter (1919-1997), who practiced with her husband Edgar in Hanover, New Hampshire and later in North Carolina. A glamorous, full-color spread in the December 24, 1956 issue of LIFE magazine described her as “one of the country’s few successful women architects” who designed her own home to “suit her own needs as mother, cook, and laundress” (but conspicuously not as an architect?). Despite the magazine’s depiction of her through photos as a mother and woman of leisure — all of the images are of her in the fabulously 1950s kitchen with her children or reading in her living room (chock-full of drool-inducing Jens Risom and Herman Miller furniture, by the way) — it does credit her for the innovative layout of the home, with the kitchen at the center and an open layout.

Family residence of architect Rebecca Wood Esherick Watkin, Kentfield, CA. Her office with drafting table and desk. Photograph ca. 1955. “Rebecca Wood Watkin Architectural Drawings, 1940–1989,” Ms1995-009. Courtesy: Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Library, Blacksburg, VA.

But one of my favorite spaces of this era that a female architect designed for herself is the family residence of architect Rebecca Wood Esherick Watkin (1913-2010) in Kentfield, California. Wood Esherick Watkin worked for her husband’s firm in the 1940s after earning her own architectural license, enabling her the flexibility to raise their three children and also to design their own residence in 1950, including her office. The room was located at the gable of the upper floor of the boldly modern home so that “mother can work in privacy (no children allowed upstairs),” noted the June 1956 issue of Progressive Architecture. It featured a wall of floor-to-ceiling glass with double doors leading to an outdoor deck, exposed wood rafters, and ample workspace for drafting. The office was light-filled with inspiring views, and thanks to the creative layout of the house it was simultaneously secluded and away from the kitchen and children’s playspaces, yet still open and well-connected. It was, undoubtedly, a room of her own.

Looking for more info? Give these reads a lookover:

For Career Women, a Hassle-Free Haven by Christopher Gray, NYT

From Tipi to Skyscraper: A History of Women in Architecture by Doris Cole

“On the Fringe of the Profession: Women in American Architecture” by Gwedolyn Wright in Spiro Kostof's 1977 book, The Architect: Chapters in the History of the Profession