From There to Here: Immigrant Female Architects

Sibyl Moholy-Nagy naturalization paperwork, 1938. Courtesy of Ancestry.com

By Kate Reggev

Here on Madame Architect, the idea of being an immigrant is at the core of our origins: dozens of interviews are with people not originally from the United States, and our intrepid founder Julia’s own background as an immigrant in need of mentorship was a major impetus for starting MA.

But when we look back at most early female architects — few though they were — things look a bit more homogenous. While they must have stood out in a room full of men, these women often had much in common with their male colleagues and counterparts: they were virtually always white, came from families of at least some (if not lots) of means, and were native-born Americans. Renowned California architect and winner of the 2014 AIA Gold Medal Julia Morgan (1872-1957), for example, was born in San Francisco to well-to-do parents originally from the East Coast; Louise Blanchard Bethune (1856-1913), the first female member of the AIA in 1888 and partner at Bethune & Bethune in Buffalo, NY, was born in Waterloo, New York to a family of Northeast educators.

Even around the turn of the century when women began trickling into architecture programs across the country, they were most often white, at least middle class, and daughters of native-born Americans. Bertha Yerex Whitman (1892–1984), for example, was the first female graduate from the University of Michigan’s architecture program in 1920 and the daughter of a local train station master in Newaygo, Michigan.

On the one hand, this shouldn’t be too surprising: few women in the late 1800s were given the opportunity to receive an education, let alone work in a white collar profession like architecture, and those who could came from families that had the funds, progressive(ish) mindsets to allow women to be educated, and access to education and opportunities to do so. In some ways, this was just a reflection of American demographics of that period, especially for those in professional fields.

An exception to this trend was Sophia Hayden (1868-1953), who was born in Santiago, Chile to a Peruvian mother and American father. After moving to the United States to attend school in Boston, she matriculated at MIT, where in 1890 she was the first woman to graduate from the school’s architecture program. We’ve already talked about her award-winning design for the Woman’s Building at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, but it’s important to note that the selection committee for the project did not see her as an immigrant or foreigner; they stated that although she was “of Spanish extraction, and a native of South America,” thanks to her education in the United States, she was seen as “essentially an American girl” (TBD on how Hayden viewed herself!). It seems likely that this interpretation of her background — probably reinforced by her physical appearance, English-sounding name, and ability to speak English without an accent — helped her win the commission as well.

By the turn of the century, successive waves of immigration throughout the 1800s (initially from Ireland and Germany, and then later from Eastern and Southern Europe and beyond) changed the demographics of the United States. Over time, this trickled down to the makeup of those attending design and architecture schools — and ultimately those who started practicing architecture.

Starting in the early 1900s, a handful of women who had originally been educated in Europe immigrated to the United States and, in some instances, continued to work as architects. Edith Mortensen Northman, for example, was born in Denmark in 1893 and moved to the United States with her family in 1914 after attending art school in Copenhagen. She discovered her interest in architecture while working as a librarian, and then used her art background to find work as a draftsman (ahem, draftswoman!) in the late 1910s and 1920s. By 1920, she had moved to Los Angeles and worked as a chief drafter, where “women in architects' offices were somewhat curiosities,” she noted. After getting licensed in 1931 and becoming one of the earliest female architects in Southern California, she opened her own firm. Despite the Great Depression, her career during this period was described as “remarkably successful,” with projects that included high-end residential (a large expansion of a Beverly Hills actor’s mansion — glamorous!), hotels and religious buildings, and a prototype for more than 50 service stations for the Union Oil Company (talk about range!).

1934 Patent for a service station by Edith Mortensen Northman.

With the outbreak of World War II in Europe in 1939, the United States gained Bauhaus greats like Neutra, Gropius, Breuer, and van der Rohe — and also several female architects who had been educated and practiced abroad. Like their male counterparts, many of these women were fleeing Nazi rule and came to the United States as refugees. Despite this status, several had long and successful careers here, like Modernist architect Elsa Gidoni and the trailblazing Sibyl Moholy-Nagy (who we previously discussed here!).

While many of these women brought with them the Modernist aesthetics taught in their schools, they often struggled to find their professional footing in the new country. One can imagine the challenges: a new language (why is nothing in English phonetic?), new friends and a professional network (so intimidating!), a new way of living (do Americans really eat Spam?!), and likely also feelings of loneliness, not belonging, and missing home — not to mention the frequent stereotyping, discriminations, and even verbal and physical abuse that many immigrants had to deal with because they were perceived as “different.”

On top of that, if finding a job in one’s field of study or work was challenging as a male immigrant, you can imagine that it was even more difficult for women. Remember that into the 1940s and 1950s, a woman’s place was typically seen as the home rather than the professional world — especially for fields like architecture that engaged with physical labor and construction. As a result, several women sadly appear to have stopped practicing once they arrived in the U.S., such as landscape architects like Hanny Strauss and Helene Wolf, who practiced as “garden architects” in and around Vienna and fled Nazi Germany in the late 1930s.

Other female architects took whatever jobs they could find, even if it didn’t relate to architecture. Lilia (Sofer) Skala, for example, escaped Nazi-occupied Austria in the 1930s and worked in a New York City zipper factory after her arrival, despite holding a degree in architecture and engineering from the University of Dresden and later practicing architecture in Vienna. While Skala never returned to architecture, fear not: her successful acting career took off in the late 1940s and 1950s and was probably way more exciting and dazzling than architecture!

Melita Rodeck, 1970. Courtesy of IAWA Archives.

For some women, though, it was just a matter of time before they were able to find their way back to the field. Melita Rodeck (1914-2011), for example, completed a degree in architecture at the Polytechnic Institute in Vienna in 1936 and immigrated from Austria in 1939. It appears that she spent the first four years after her arrival volunteering in low-income neighborhoods New York City before finding work as a draftsman at a firm in Buffalo, New York; she eventually settled in Washington, D.C. in 1950, where she worked for the General Services Administration (GSA) and became licensed in 1952. By 1958, she had built up enough of a network that she was able to open her own firm, Melita Rodeck & Associates. While Rodeck saw lots of success in her firm — she completed renovations and ground-up projects for residences, religious institutions, and government facilities, her local chapter of the AIA, on the other hand, wasn’t the supportive organization she hoped for — she recalled being the only woman at meetings and being entirely ignored by her (male) peers).

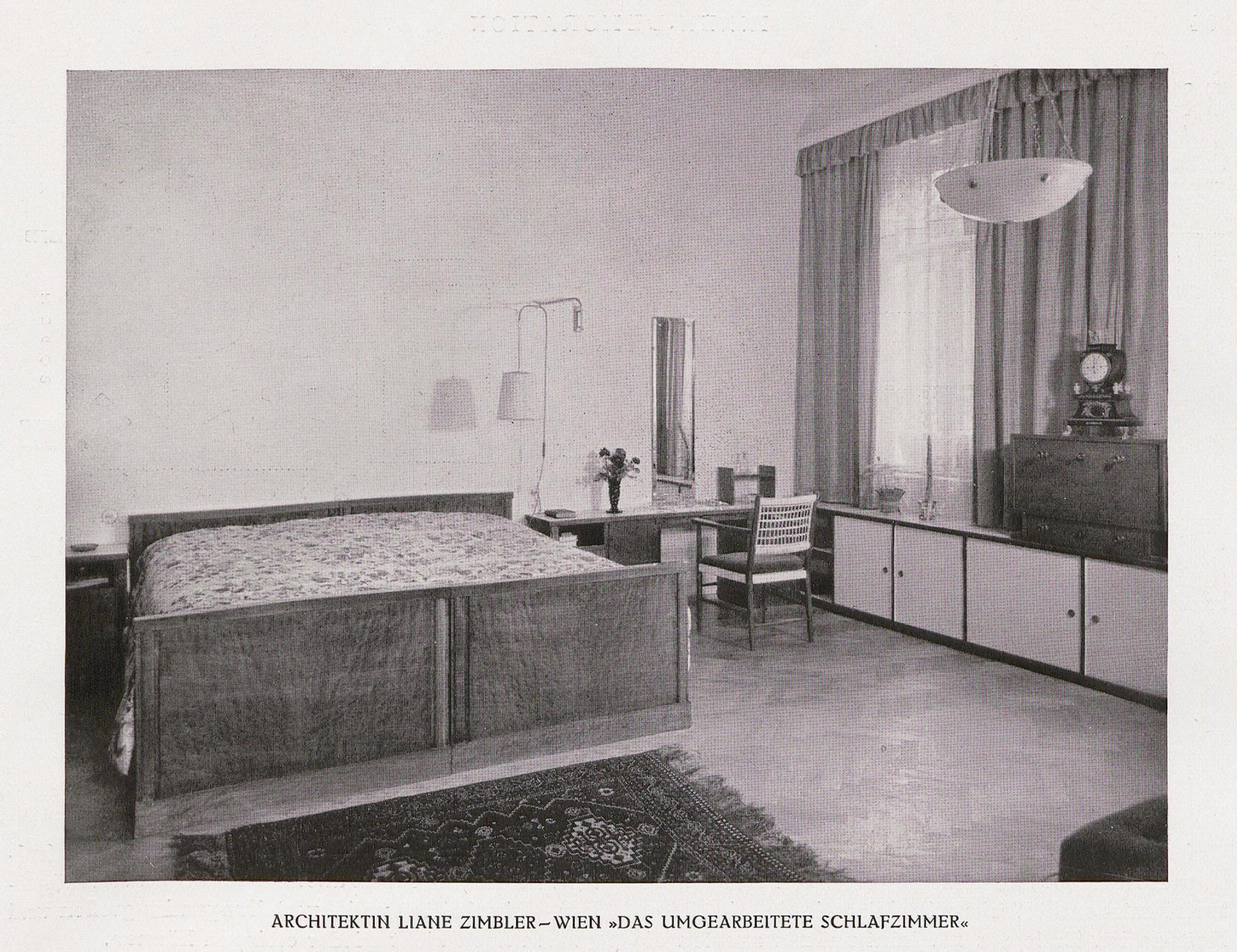

Liane Zimbler, modernization of a bedroom in a Viennese apartment, state after, 1934, reproduction from Liane Zimbler, »Elegantes Schlafzimmer« von 1910 ‒ Modernisiert, Innendekoration, 1934, vol. 45, p. 302.

Similarly, Austrian architect Liane Zimbler (1892-1987) left behind her successful architecture and interior design practice in Vienna in 1938. She initially worked in a wrapping paper company until she managed to find a position at the office of interior designer Anita Toor, thanks to some connections in Los Angeles. Within a few short years, Zimbler’s husband had died, as did Anita Toor, and Zimbler ended up taking over the firm in 1941 and continued working until the age of 90 in 1982.

An entire book could be written on the contributions of mid century immigrant female architects (no surprise here: the book about male immigrant architects in the U.S. has already been written — although this paper and the research by Dr. Tanja Poppelreuter are excellent). But in 1952, an immigration act came into effect that ended Asian exclusion from immigrating to the United States and emphasized uniting immigrant families and attracting skilled workers. As a result, the 1950s through the 1970s saw an influx of more diverse and yet also highly educated female immigrant architects — some of them extremely influential, like South Africa-born trailblazer Denise Scott Brown (1931- ), who we’ve previously discussed.

Like those who immigrated before them, the female architects who came after World War II arrived for a variety of reasons: political instability in their home country, educational and professional opportunities, the promise of a fresh start, the new job of a family member, and more.

Nezahat Sügüder Arıkoğlu. Courtesy of Baltimore Architecture Foundation.

Among the women who arrived during this period was Nezahat Sügüder Arıkoğlu (1920 - 2000). Arıkoğlu was educated in her native Turkey and immigrated to the United States with her architect husband, İlhan Muzaffer Arıkoğluin initially in 1947. The couple stayed in the United States for three years before returning to Turkey, only to come back in 1960 when her husband was offered a position at the Whiting Turner Contracting Company in Baltimore, Maryland. Arıkoğlu soon worked with her husband as the company’s Chief Architectural Designer before they opened a well-respected firm together in the late 1960s. During their time in the United States, they completed more than 30 projects in the Baltimore area before returning to Turkey in the early 1970s, where both their son and grandson were inspired to follow suit and practice architecture.

Architect Milka Bliznakov (1927-2010) similarly left behind an architecture practice before her move to the United States in 1961. She left Bulgaria in 1959 due to political circumstances — in fact, on her immigration paperwork, she stated that her nationality was “stateless.” After completing her Ph.D. in architectural history at Columbia, she went on to have an impactful teaching career. Like many immigrants, her background heavily influenced her professional choices; she developed an expertise in the avant-garde and Russian Constructivism, which stemmed from her upbringing and time in Bulgaria (the country was closely allied and one of the most loyal satellite states of the Soviet Union during the Cold War). Significantly (for nerds like me!), she also had a strong interest in women in architecture, and established the remarkable treasure trove that is The International Archive of Women in Architecture at Virginia Tech in 1985.

Others who arrived during this period women sought to continue their studies. Argentinian-born architect and historian Susana Torre (1944- ) also arrived in the United States in the 1960s, initially through a design conference and fellowship from the Edgar Kaufmann Jr. Foundation in 1967 and then subsequently to complete postgraduate work at Columbia (by this point, though, she was encouraged by professors and friends to remain in the U.S. because of the “dirty war” in Argentina at the time). Soon, she was completing research for the Museum of Modern Art, teaching at SUNY Old Westbury, and founding the Archive of Women in Architecture of The Architectural League of New York, which led to the 1977 exhibition “Women in American Architecture: A Historic and Contemporary Perspective.” While she never returned to Argentina to live full-time, her formative years in South America were the impetus for much of her writing and research, which focuses on Latin America and feminism. In an interview in 2002, Torre noted that she had “lived more than half of my life in the United States” and was “completely bilingual and bicultural” — a testament to the multifaceted nature of being an immigrant and to the staying power of one’s origins.

But generally, most women rarely spoke — at least, publicly — of the difficulties they encountered as immigrants, or how they felt about the move and transition to a new country. Certainly they must have been aware, to some degree, of how they were perceived; the son of Nezahat Sügüder Arıkoğlu, Kaya, recounted that as a student in architecture school, he thought of his mother and her strong accent, as a “lady from the Old Country,” and therefore underestimated her work and abilities.

On the other hand, when asked about her move from Japan to the United States at the age of 14 in the 1960s, architect Toshiko Mori (1951- ) simply said that “it was a very, very big change,” especially because English at the time wasn’t her strongest subject in school. Is this an understatement? Mori was born in 1951 in Japan, where the effects of World War II’s devastation and scarcity were still felt, in contrast with the U.S.’s economic postwar boom. Or perhaps Mori, like many others, felt a pressure to assimilate and minimize that which made her different, or a desire to move on and focus on the future — one can only postulate. But regardless of how they described their experiences, all of these women brought with them fresh ideas, the impact of their home country, and the desire to be a part of something new.

Additional Resources

“Over the Ocean: Women Immigrants in American Landscape Architecture in the 1940s and 1950s,” by Ulrike Krippner

Émigré Cultures in Design and Architecture (2017), Alison J. Clarke, Ed. and Elana Shapira, Ed.

“German-speaking Refugee Women Architects before the Second World War” by Tanja Poppelreuter

Architectural Record March 1948

Diane Favro, "A Region for Women: Architects in Early California," Architecture California, February 1991.

Marcia Feuerstein. “An Interview with Susana Torre,” in Reflective Practitioner Issue II, Virginia Tech, 2002.

Ladislav Jackson, The Pleasure Of 90-Years-Old Before And After Pictures, Or The Rise Of Upcycling And Zoning In Liane Zimbler’s Living Space