Achieving Alignment: Andrea Steele on Testing the Waters, Design Excellence, and Sharing Learning

Photography by Ben Salesse

by Julia Gamolina

Andrea Steele is the Founding Principal of Andrea Steele Architecture (ASA), a New York-based practice that believes the scale of architecture is not measured by its physical size, but by its positive impact on people, resources, and sense of place. With over two decades of experience practicing architecture, Andrea Steele has led a wide range of complex urban design projects throughout the United States. Steele served as partner and principal of TEN Arquitectos’ New York office for more than eight years before renaming the studio in 2019. As Andrea Steele Architecture, the studio continues the design rigor and excellence, with a heightened focus on institutional, cultural, and community-oriented projects.

Andrea Steele received her Master of Architecture degree from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. She has taught at Cornell University, City College of the City University of New York, and the Catholic University of America. Steele lectures widely throughout the United States and is a frequent participant in academic juries. Steele is currently an advisor to both the Urban Design Forum and Pioneer Works. In her interview, Andrea talks about her experience starting offices and juggling multiple identities, advising young architects to find the learning and the humor in things.

JG: What was the first spark of your interest in architecture?

AS: The interest was a natural evolution of who I was. My parents met as Peace Corps volunteers in India, so I was raised, in New Jersey, with the understanding and the belief that you had a social responsibility. My father was the father who said, “There are starving people in Africa.” Then on the other side, my grandfather was a very strict Naval Chaplain - he believed so strongly in math and science. Every week when I would visit him, we’d play games - backgammon, chess, checkers - and he would quiz me on my knowledge of science and math.

I began my college studies in Biology with hopes of pursuing a career in Neuroscience. I believed that a deeper understanding of the brain - the mechanism with which we understand ourselves and the world around us - could help me identify methods to improve people’s experiences.

New York Public Library 53rd Street Branch © TEN Arquitectos/Enrique Norten

New York Public Library 53rd Street Branch © TEN Arquitectos/Enrique Norten

How did you finally switch your focus to architecture?

While studying biological sciences, I had to take an art elective, and so I took an architecture studio. I remember being told no one takes an architecture studio as an elective [laughs]. Very quickly, I realized why that was – but more importantly, I came to the conclusion that I could directly influence and improve people’s experiences by designing the world around us. By engaging the mind and body through a carefully considered built environment, I could have a positive impact on the individual and collective.

I wrote my graduate thesis at the GSD on how understanding the brain can assist us in our design. If you were to walk into my library now, half of my books are on architecture, the other half on neuroscience. Most people are surprised and ask how I would have two such diverse interests, but I see them as very similar – both seeking to create connections.

They don’t seem so different to me at all. Given this background, what was your first job in the industry, after the GSD?

After graduating, I went straight to Baltimore, which was an unusual choice and raised a lot of eyebrows. Everyone else in my class went to Boston, New York, San Francisco, Chicago, or LA. The short explanation is that my college roommate was from Baltimore and I had promised her I’d move south.

It proved to be a smart move. By going off the beaten path, I ended up at a firm that handed over huge responsibility. I remember my interview with the partner to this day - he said, “We’ll give you just enough rope to hang yourself.” And what an odd thing to say to someone you want to join the firm!

“...sharing learning is one of the strongest connections you can make with someone. When you can learn together, that builds trust and the bonds that last.”

And to a young person interviewing for their first job [laughs].

Exactly. But they did what he said! They handed over the master plan for Southeast Baltimore and a new ground-up administration building for an all-girls school on a Marcel Breuer campus.

To be honest, a lot of times I found myself dangling because I had jumped in so quickly. But that’s where I discovered the value of mentorship. At that moment in time, I was working with the two women partners in the firm, both of my clients were women, the contractor building the school was a woman, and a trained architect. She took me under her wing and really walked me through everything - my learning curve was practically vertical. I realized that the relationship between a contractor and an architect didn’t have to be and wasn’t an adversarial relationship at all.

I did not know then that being surrounded by all these women, all of whom were thought leaders and decision makers, was a unique condition. Since that time, twenty years later, I have not been in a similar situation. Sometimes I wish I could go back and soak it in, realizing that it isn’t always the case.

That’s an amazing foundation. What did you do with it?

I did what many architects do - I decided to move to New York. I went back to my firm and said “I love it here, but feel it is my time to move on.” In response, they did something incredible - they turned around with a counter proposal and said, “Will you open up an office for us there?”

I did, and Barbara Wilks, one of the partners and mentors I mentioned, came with me. Around that same time, we met Enrique Norten - he wanted to test the waters in the US for TEN Arquitectos, which is based in Mexico City. Both Barbara and Enrique wanted to see what New York had to offer, so I, effectively, opened up a joint office for them in Dumbo. At the time it was called “TEN + W”, which eventually became two firms: TEN Arquitectos in New York and W Architecture & Landscape Architecture.

Make the Road New York © TEN Arquitectos/Enrique Norten with Andrea Steele Architecture/Andrea Steele

New York Restoration Project Casita © TEN Arquitectos/Enrique Norten

What did opening up an office in New York mean, in this instance?

Everything [laughs]. Building the desks, setting up the equipment, identifying the opportunities. We were all new to New York and needed to figure out who all of the players were. I also learned what having an office in New York meant in terms of opportunities. If you have a New York address, it gives you the credibility to work anywhere. The New York address became a gateway to a larger, global mindset.

People ask me now, and people asked at the time, “Wasn’t it scary to start?” My lack of hesitance at the time was probably more ignorance than courage - I was only two years out of graduate school! But I had the support of Barbara and Enrique, and my role really was to be boots on the ground to identify opportunities and bring good people. And I delivered; I brought amazing talent to create the inaugural studio, and then it developed from there.

At some point then, you ran your own firm for a while.

Yes - after I put this joint office together, and it started to take off, I left [laughs]. I was pregnant with my first child.

You have no idea how many women I’ve spoken to that start their own firm because they’re about to start a family. Almost every single mother I’ve interviewed.

When I gave Enrique and Barbara the news, I joked that I was leaving to have my son and start my own firm, because how hard could either be? [Laughs]

I’ve noticed that often times, when you have a big change in one part of your life, other big parts change too. Did you go back to working for an office eventually?

I did. I had always been interested in how the built environment can enhance our process of learning, so I made a conscious decision to go back in-house and work at a firm that focused on schools, Murphy Burnham and Buttrick. Right away, I started on the School of the Holy Child.

I took that project from concept through construction. This project was a turning point for me. The engagement I had with the client led, not just to a successful project, but to many lasting relationships. Those relationships inspired me to strike out on my own again. For six years, my studio focused on academic and residential work. I never marketed; I got projects through word-of-mouth and we were always busy. I went on to complete three other projects for Holy Child. In fact, my design process with the school community prompted it to expand its curriculum to include Architecture, Engineering and Design for the Common Good, a STEAM program for which I taught the inaugural class.

“Alignment builds trust and community; it is the ultimate goal of both the process and product of architecture.”

That says a lot.

Yes. Then one June afternoon - I can remember how sunny it was because I was lucky enough to be sitting outside working - Enrique called. He said, “I know you’re doing well. So are we, and I would love for you to bring your practice and oversee the TEN Arquitectos New York studio and be my partner.”

The interesting thing was, he insisted I maintain my name and my practice. He was concerned I would feel that I lost my identity in the merger.

So you were essentially operating two firms at the same time?

Yes. I had two sets of clients, two emails, two sets of staff - yet I was the same person, and I had the same ideals. In essence, the studio became one and all of the staff integrated. Eventually, I went to Enrique and said “I don’t care whose name is on the door, I just want to be running one studio and working together towards one mission.” So, for eight years, I ran the TEN Arquitectos New York office as Managing Partner. Over that time, Enrique and I collaborated on the design of 50 to 60 projects, and saw over 20 projects built.

Through all that, I began to notice that even though our design philosophy was the same, how we ran the practice was very different.

How so?

I loved the mentoring aspect of it. For me, a crucial part of the design process is spending time with staff and clients. That’s where the design starts. A successful project needs a successful process which can only happen if your client understands and trusts the process.

AIANY WIA 10th Annual Women in Architecture Recognition Awards Ceremony

Andrea in Studio © Carolina Madrigal

Walk me through the transition from TEN Arquitectos New York to Andrea Steele Architecture.

At the beginning of 2019, I felt I had come to the end of what I thought I could contribute to TEN Arquitectos. I posed this to Enrique, who at that same moment was coming to the realization that he wanted to focus his efforts on his international practice in Mexico. So, we decided to separate. In the summer of 2019, I took over the former New York office of TEN Arquitectos. It officially became Andrea Steele Architecture (ASA).

The decision was very positive and very natural. Positive, because both of us have thriving offices, me in New York and Enrique in Mexico City. It is also natural, as I am continuing with the same staff, same clients, and same projects.

With establishing ASA, where do you feel like you’re in your career today?

At this moment, I would say I am at once at the beginning, middle, and end. Beginning, because we have just begun working with several incredible community and cultural groups that are seeking the hands-on, immersive process that is so fulfilling to me and my studio. Middle, because I have never changed my values and where I see the power of architecture. End because I no longer see my practice solely dependent upon clients coming to us with the projects. Our studio will always welcome clients bringing us new opportunities, but since the transition to ASA, we have initiated several projects where we are leading the programming, business planning, and implementation.

How are you doing that?

We have partnered with social impact entrepreneurs and real estate developers to work with local communities to define a new transparent development process and structure that puts these community groups in a position of co-leadership and co-ownership. I am hoping this translates into a new value proposition for our firm and the profession as a whole, not only to tap into our insights and talents that are often unrecognized or underutilized, but also to bring needed design resources to the public who might otherwise not have access to architects.

“There is no such thing as neutral action - it’s up to you to move design excellence forward.”

Looking back at your career thus far, what would you say have been the biggest challenges for you?

Achieving alignment. Between our first site visit until the ribbon cutting, we must engage with hundreds, if not thousands of people during the course of a project’s development. Not one of these individuals comes to the process with the same agenda, experience and engagement with the project. Yet every one of them, in some way, needs to understand the vision and goals to move the project forward. If you aren’t aligning at every step, misunderstanding can occur and concessions result.

Alignment builds trust and community; it is the ultimate goal of both the process and product of architecture.

What about the biggest highlights?

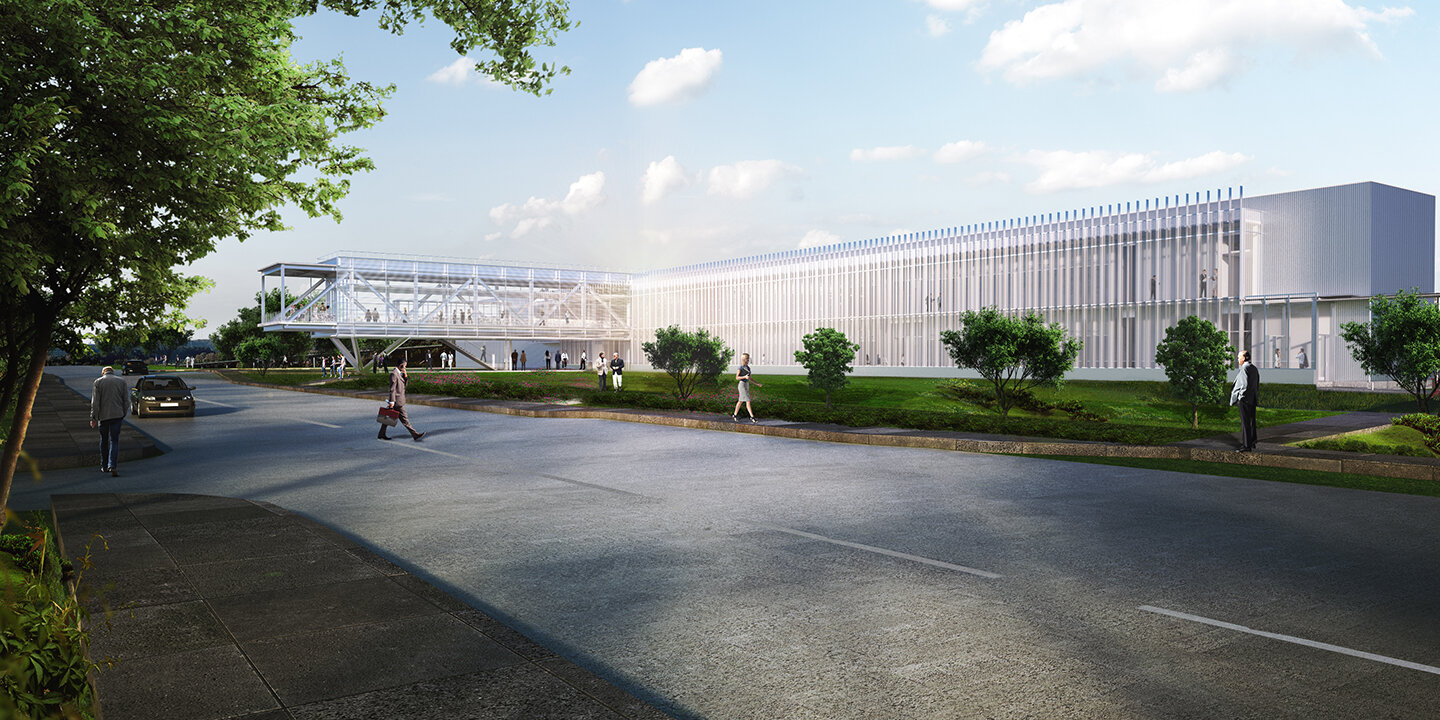

I would answer the same. Achieving alignment! Our NASA project was one of the greatest examples of this, and yet I know that once the project is done, I will do what I have always done – put the images on our website - and that documentation is going to represent, presumably, what we’ve achieved.

What I’d like to figure out is how to document how we create alignment. Most of the really good achievements don’t happen in the public eye. They happen in a meeting room, on a construction site, when you make that connection with someone and they realize how the design process and project can elevate their collective community and individual aspirations.

NASA Glenn Research Center Support Building © TEN Arquitectos/Enrique Norten with Andrea Steele Architecture/Andrea Steele

Taxi & Limousine Commission Garage and Inspection Facility © TEN Arquitectos/Enrique Norten

What would you say your general approach to your career is?

We had a wonderful group of interns this summer, cataloguing all of our work graphically for a proposal. One day, I overheard one of them saying, “We’re only drawing what’s known.” Like it’s not design. The next afternoon I called the whole studio into the conference room and said, “If you ever find yourself writing meeting minutes, or managing a client, or generating a rendering, and say to yourself that what you’re doing is not moving design excellence forward, you’re right. Not because you shouldn’t or can’t with this exercise, but because you aren’t. There is no such thing as neutral action - it’s up to you to move design excellence forward. You’re either moving us collectively and individually forward, moving our design forward, or you’re moving it back.”

Creating a rendering is not depicting a building - it’s translating ideas. These are design questions. Of course, it’s not creating the concept of the building, but you’re designing. Everyone contributes to design excellence - when you’re reviewing a shop drawing, you’re making sure that it reflects the vision; when you’re creating meeting minutes, you’re confirming the communication that supports the collective alignment. You should always be asking yourself, “Is there something that I can contribute at this moment in time that improves the design?” It’s all design. It all contributes to design. There is no neutral.

Finally, what advice do you have for those just starting their careers?

Find the humor in things. And the learning in things. Sometimes that learning is learning to laugh. Make new mistakes, not the same ones. I know what motivates me and what propels me is the desire to learn, but learning is really about creating connections. Building relationships. From that springs forth the project. And sharing learning is one of the strongest connections you can make with someone. When you can learn together, that builds trust and the bonds that last. These last few months have been proof of that. With my recent announcement about ASA, many of my past clients are coming back to me with new opportunities. And that gets me excited for 2020 and beyond!

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.