Intimate Links: Neri Oxman on Designing Systems, Radical Change, and Architecture as Destiny

By Julia Gamolina

An architect, scientist, engineer, and inventor, Neri Oxman has led the creation of scientific research and technologies with an emphasis on integrative design across scales and disciplines. A multi-disciplinary designer, Oxman founded The Mediated Matter Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2010 where she established and pioneered the field of Material Ecology, fusing technology and biology to deliver designs that align with principles of ecological sustainability. Oxman took on a faculty position at MIT in 2010 and became tenured in 2017. Oxman received her Ph.D. in Design Computation at MIT in 2010. Prior to that, she earned a Diploma from the Architectural Association in London, completing studies at the Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning at the Technion Israel Institute of Technology, and training at the Department of Medical Sciences at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem.

Oxman worked as an architect and research consultant at Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates in London from 2004-05, during which she also served as Visiting Associate and Evaluator for SmartGeometry Group. In addition to over 150 scientific publications and inventions, Oxman’s work is included in the permanent collections of leading international museums including MoMA, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Centre Pompidou, MAK Museum of Applied Arts, FRAC Collection for Art and Architecture, and the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. Her work has been recognized at the World Economic Forum, where she was named a Cultural Leader in 2016 and is a member of the Expert Network. In 2018, Oxman was honored with the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award and the London Design Innovation Medal. In 2019, Oxman received an Honorary Fellowship by the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Contemporary Vision Award by SFMOMA.

In her interview with Julia Gamolina, Neri talks about growing up with architecture, forming her own field, and the forces that have influenced her work, advising those just starting their careers in design to consider themselves drafted by Mother Nature. For more, follow Neri on Twitter and on Instagram.

JG: How did your interest in architecture first develop?

NO: Growing up, architecture was all around us. Both of my parents practiced and taught architecture and, as youngsters, my sister and I were quite literally enveloped in the profession. My parents’ studio was located mid-way up a staircase, as if suspended, a petite atelier armed with two drafting boards, one on each side of the space. It was the best hiding place in the house, a tiny fun-palace packed with models and modeling materials.

The house itself was filled with custom framed posters and reproductions of the work of artists and architects my parents collected over the years and throughout their travels. In the living room were four works from Paolozzi, his Wittgenstein As is When series from 1964. Victor Vasarely’s Op Art was in the kitchen, and a collection of magical sculptures from Asia and Africa was dispersed throughout the house. Growing up amongst figure-ground representations of Rome circa 1550’s (two of them were hung above my parents’ bed), both Keren, my sister, and I knew what a Nolli Map looked like well before we learned how to read. Talking about Modern buildings as if they were people was a ‘thing.’ My dad would load up his Kodak Carousel 80 slide tray (he used to carry two carousels with coordinated slide decks, plans coupled with sections, sections with elevations, and so on) and narrate us through Modern Architecture as if reciting Alice in Wonderland.

And so my interest in architecture grew as I grew. From childhood through adulthood I always had a thing for design. When I joined architecture school, I sat in some of my father’s classes as a listener. He taught two classes. One was called Theories of the New Age and the other was called The Art of the Plan. Sitting in on those classes, was transformative. I realized that architecture was more than a profession, it was a kind of destiny, a way of being in the world which was all encompassing. I will forever cherish his slides and his teachings, and the way he made his students fall in love with the art of architecture.

“With my father (Prof. Robert Oxman) in our little childhood garden.” Image: Rivka Oxman.

“Lying by my mother’s side (Prof. Rivka Oxman) in our little childhood garden.” Image: Robert Oxman.

“Flipping through Reyner Banham’s “Theory and Design in the First Machine Age" as a toddler.” Image: Robert Oxman.

What did you learn about yourself in studying architecture, in Israel, at the AA, and at MIT?

I’ve learned different things from different experiences and have taken along with me the formative ones, ones I found useful, meaningful, or both. Looking back, the skills I’ve earned in one school complimented the other: the Technion taught me how to answer, the Architectural Association taught me how to question, and at MIT I learned that achieving true novelty stems from the ability to answer a question with a question.

How did you get your start in the field?

In over two decades I formed my own. Back at the AA I noticed a significant dimensional mismatch, or disconnect, between the “what” and the “how” of architecture. Especially during the early 90’s, architects and designers were creating complex building and product forms using high-end tools and technologies for design generation and digital construction, generally without much understanding of material properties or concern for the environment. This has led to a significant rift between designers and builders. Nature, of course, doesn’t have this problem; in Nature there is an intimate link between shape, structure, material and growth. They are all related. When I formed The Mediated Matter Group at MIT, I based it on a few core ideas borrowed from Nature: the first was that shape is cheaper than material in Nature, and the same should hold true for the built environment; the second was that in Nature you don’t find assemblies of homogeneous materials. In nature things are grown, not built; making biological organisms and materials―across all kingdoms of life―highly customized, responsive and adaptive to their environment.

So, this dimensional mismatch between the built and the grown, compounded with these two core ideas, enabled us to carve out a research space focusing on new techniques and technologies, new processes essential to produce products that were materially complex, environmentally responsive and easy to construct in one go. We then began working on form-generation platforms that take into consideration the properties of physical materials and environment. That got us working on new digital fabrication methods enabling the design and construction of composite structures with multiple properties―mechanical, optical, chemical and even biological―that can be constructed as a single system without assembly. This is how Material Ecology began, the very idea that all the things we produce and build are inextricably linked with the built environment.

“I realized that architecture was more than a profession, it was a kind of destiny, a way of being in the world which was all encompassing.”

Where are you in your career today?

After over a decade at MIT leading The Mediated Matter Group, I, along with my new team, are focused on building a new kind of company; partly an architectural practice, partly a scientific lab, a biotech company and a design studio. The hope is to translate our research and deploy it in the real world.

I can’t wait for the launch. As for other new beginnings, you just had your (first?) child! What have you learned so far in motherhood? How does your new role contribute to your work, and vice versa? And furthermore, should mothers be talking about motherhood as it relates to their work, or do you think the two should be kept separate?

Something changes within you when you become a mother, a parent. You are no longer the protagonist of the windy script comprising your life; there is a little vulnerable person who is dependent on you for her survival. You become further aware of your mortality and the sense of your place in time. You become smaller in a way that enables you to assume an even bigger identity in a way that removes the centrality of your identity. You are humbled by lineage and the notion that you are but a chain in an endless chain of ancestry.

I don’t believe in keeping things separate. Parents should absolutely be talking about and sharing their experience of parenthood as it relates to their work if they so wish to! The notion that one must bound oneself and resist the desire to share or express one’s personal experiences in a professional context I find abrasive, unproductive.

“With one of our alumni, Will Patrick at our Synthetic Biology module for Design across Scales, an Institute-wide class I held at MIT in collaboration with my dear colleagues, Prof. J. Meejin Yoon and David Sun Kong.” Image: David Sun Kong.

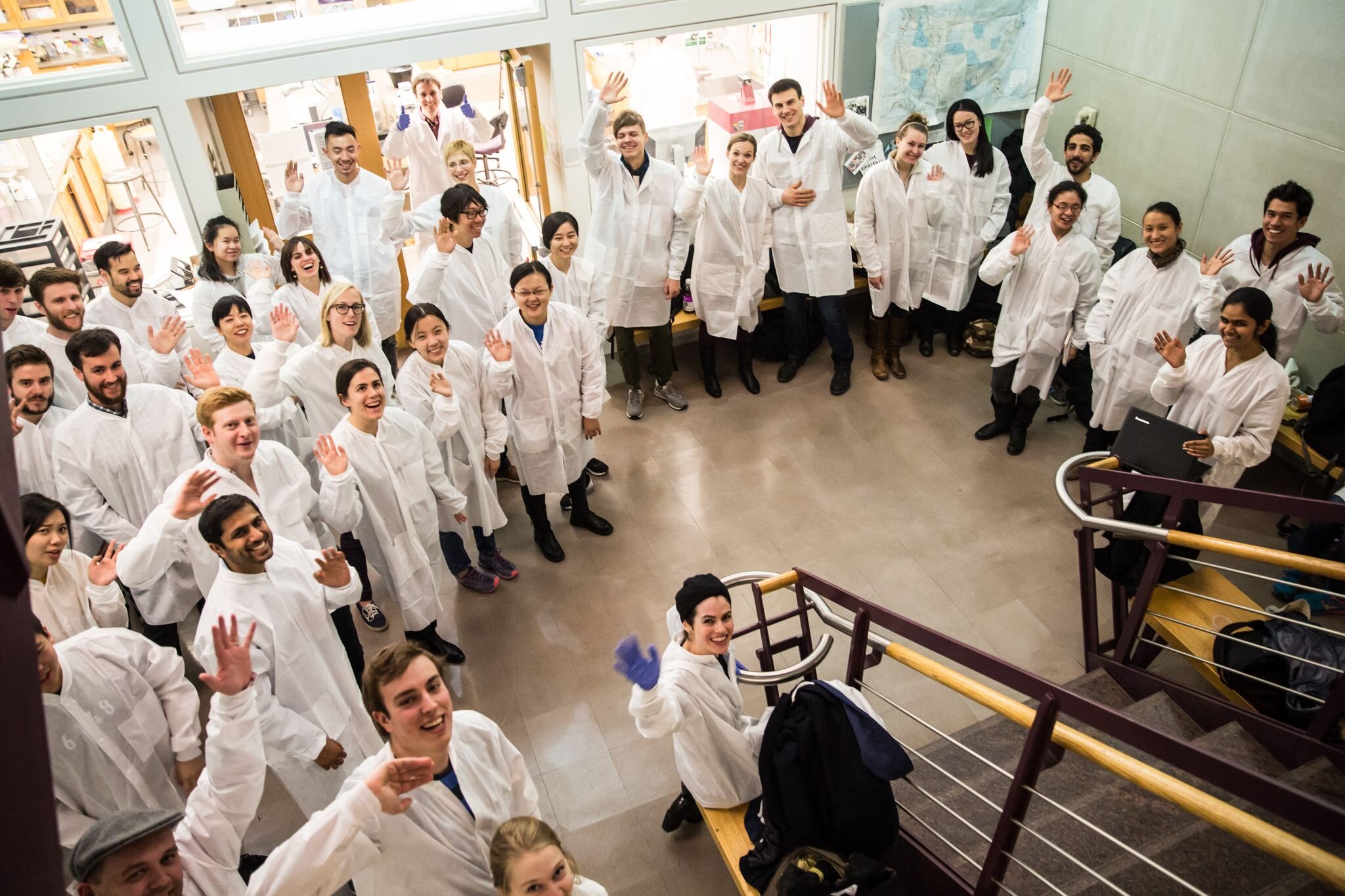

“With our students and alumni at our Synthetic Biology module for Design across Scales, an Institute-wide class I held at MIT in collaboration with my dear colleagues, Prof. J. Meejin Yoon and David Sun Kong.” Image: David Sun Kong.

“With our students and alumni at our Synthetic Biology module for Design across Scales, an Institute-wide class I held at MIT in collaboration with my dear colleagues, Prof. J. Meejin Yoon and David Sun Kong.” Image: David Sun Kong.

Looking back at it all, what have been the biggest challenges and setbacks for you?

The biggest challenge is jumping, the biggest setback―looking back. As I reflect while looking forward, perhaps the most meaningful of challenges were and are the ones associated with making something new: a new process, a new product, a new kind of technology that will hopefully make a real difference in people’s lives.

I am quickly learning that the place where one is called upon to innovate―outside of academia and in the real world―gets lonely quickly. The industries surrounding the built environment, especially in the fields of architectural design and construction are now threatening our very existence. We need to radically address what we design and build, how we design and build, and why. When I first established my Group at MIT it was me, my pencil set and a bunch of lab equipment. We now have a major show at MoMA, and are in the process of setting up a new company. There’s no doubt in my mind that the only way to cross the Rubicon is to fly over it, reassess the field, help redirect it, help rebuild what has been harmed and grow the profession anew.

What have been the biggest highlights?

Life itself, the simple things about it: laughing loudly with my daughter, mountain biking with Bill, reading Tolstoy under an apple tree, sketching with my team. Getting married, giving birth, and starting a company; all within one year more or less.

“...true novelty stems from the ability to answer a question with a question.”

Who are you admiring right now and why?

Bill Ackman, my man, my hero, my inspiration. He is more truthful than truth itself. He embodies a wholesome balance of self-confidence and self-effacement which enables him to find foresight in work and in life; that is what makes him a good leader. He also gets the big picture and doesn’t spend time on regrets. He always moves forward, and always with positivity. From Bill, I’ve also learned the precious lesson to listen to others, but to make my own decisions, and to take responsibility for those decisions. He has also shown me the power of unforgiving forthrightness; the quality of being as transparent to others as I am towards myself about important crossroads in life and work. My love for him contains so much admiration for who he is and what he stands for, and I feel very lucky to have found him.

Maestro Francis Ford Coppola. I admired Francis before I met him, and even more after I met him. He is one of those larger than life creators who exist beyond time, who can approach the new world through the old world. For almost all of his films there are so many arcs and arches and landscapes of stories, but, in the end, the story is very simple: love, loyalty, imperial decline. He is Shakespeare in moving image. An inspiration for every architect aiming to build the world anew while relishing the family unit, true love, the art of making pasta, scripting a classic kiss.

Ohad Naharin [Israeli contemporary dancer and choreographer, previously the artistic director of Batsheva Dance Company.] I find his sense of self-awareness unrivaled. When I say that I miss Israel mostly when I am there…what Ohad embodies or represents―that is what I miss… the old country, when children shared a sleeping quarter (in the kibbutz) and farmers would milk cows together and life was simple in its beauty and also in its ugliness. Ohad brings that virgin childhood into his dance. He knows how to let go of the intellect allowing dance to be about dance. He is a shaman of the human body, and he is a genius at it.

Barbara McClintock, who won the Nobel Prize for Physiology in 1983 for the discovery of “jumping genes,” that genetic information is not stationary (genetic elements that can “jump” to different locations within a genome). Her biography is a must read, a woman ahead of her time.

My team. They are family to me, and I feel very lucky to be working with such brilliant minds: Sunanda, Christoph, João, Rachel, Nic, Felix, Anran, Nitzan, Dee and many many more. None of our work would be made possible without the beautiful mind space we occupy when get together. It’s pretty magical. And, as Arthur C. Clarke so thoughtfully declared, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

“If you’re thinking about a career in design, make it a calling; consider yourself drafted by Mother Nature. To engage with the built environment is no longer only about designing buildings and cities. It’s about designing systems that have the ability to impact our lives across every scale.”

Word is that you’re a film connoisseur and enjoy considering your architectural interventions as scenes in a film. What are some of your favorites?

FFC’s The Godfather. A tragedy of imperial decline with a Ninor Rota soundtrack, cinema doesn’t get better than that! Can’t think of a better way to explore and express the painful duality between law and order, justice and loyalty. A modern-day Shakespeare's King Lear at its best.

Fellini’s 8½. All creators should watch this film and feel good about the bad days. It is essentially about finding yourself in the face of public scrutiny and expectations, with incredible music (Rota again) and gorgeous set designs by Gherardi.

Kubrik’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Meejin [Yoon] and I held a class in our Design across Scales dedicated to this film alone. An epic masterpiece for the mind, the eye and the ear. I don’t know what’s better: [Arthur C.] Clarke’s original text or Kubrik’s vision. My favorite sequence is by far the Dawn of Man condensing in about 8 seconds, two hundred thousand years in 105 shots.

Fellini’s La Dolce Vita. Favorite scenes are the 1st Day Sequence with the helicopter transporting a statue of Christ over a Roman aqueduct, and Anita Eckberg in the Fountain of Trevi – juxtaposing technology and tradition, mortal and immortal beauty.

FFC’s Apocalypse Now. On the jungle and human dissolution into madness. Conrad's Heart of Darkness envisioned as a Vietnam War Film with one of the most important scenes in cinema, blasting Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries while resuming “death from above” ... Charlie’s Point is humanity’s heart of darkness … If I recall correctly Dennis Hopper’s lines to Kurtz were authored on the fly … and Brando’s as well. The best combination of acting and directing.

Nichol’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. A black comedy drama set to Edward Albee’s play. Taylor and Burton’s performances are painful to watch, but profound in their message. When I am sad or upset, I often repeat to myself “What a Dump!” (with Taylor’s intonation), laugh a little, cry a little, and get back to work.

Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander. Because it reminds me of childhood and growing up in my grandmother’s garden. And because Strindberg’s A Dream Play is one of my favorite texts.

With The Mediated Matter Group and the OXMAN team at the Opening of our show, Material Ecology. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Image: Bill Ackman.

With team members from The Mediated Matter Group looking through Aguahoja I. Image: The Mediated Matter Group.

Beautiful. Zooming out now, what is the impact you’d like to have in the world? What is your core mission?

To radically change the design landscape from the ground up. To question the very nature of how we make things, and how we can make them in different and better ways; for us, for the planet, for other species. That is why I am forming a new company.

I recall years ago asking Osvaldo, my former husband, at which point does he consider his musical compositions to be considered successful. His answer was profound: “When I move my audience and make them cry.” I think with art, it only takes one. When you have moved a single individual to the point of laughter, or tears, or a state of deep reflection, you have made an impact. Similarly, with science, arriving at a beautiful equation is the act of inhabiting a higher plane. I am a great believer that the things that are least important for our survival are the very things that make us human (per the wise and wonderful Savas Dimopoulos).

Achieving technological impact on a global scale by design is at once similar and different. The goal with technology is—in addition to insight—enablement. In addition to reflection—transformation. Once you have empowered and enabled an entire population to question how and why they live the way they do, you have made an impact. And I have always attempted to embrace and promote both insight and enablement, reflection and transformation. In the end, design is the practice of artful enablement. It’s where science and engineering unite to the point where one can no longer differentiate between product and process.

What is your general approach to your career, and by that I just mean what is the core philosophy you come back to when facing challenges, making decisions, things like this.

In my core, I am a spiritual person, and I like to assume the centrality of flow; the state of awareness one reaches when knowing the way forward even, and especially when, it is unknown; That embracing ambiguous circumstances is a skill, that gratitude is a gift, that a successful leader leads first and foremost with love, that kindness is the ultimate currency. In the face of challenge, I return to first principles. These are values I swear by, both in my personal and in my professional life. I have learned over the years that when the mind, the heart, and the gut disagree, one is simply lagging behind the other. So I wait for the lag to resolve itself. It is from this place of harmony and a deep and peaceful sense of knowing that you can face the hardest of challenges. I’ve also come to accept that in order to make meaningful impact in the world, one must be willing to sacrifice the image of one’s existence in that world accepting that one may not live to see and experience it.

Important advice for challenging times: learn who your real friends are; listen to your inner voice (it is the quietest voice); learn when to let go (of anything or anyone); accept that most individuals you deem unkind are merely weak; lead with love; cope with compassion; when called for: trade ambition for patience and patience with self-care. Remember that love begets altruism, and self-sacrifice begets humanity. And that humanity is our most precious cargo.

And, finally, the moon. A very wise woman once shared with me that in her experience every decision we make, from the time we are born to the time we pass, is guided by the moon. So when I question, I look up. There is a sense of inevitability in the moon, and in general, in letting nature run its course. In other words, I am tenacious in my nature, and I don’t easily give up on people or things, but at the same time I can make peace with fate when I am called upon by destiny.

“I have learned over the years that when the mind, the heart, and the gut disagree, one is simply lagging behind the other. So I wait for the lag to resolve itself. It is from this place of harmony and a deep and peaceful sense of knowing that you can face the hardest of challenges.”

How should the architectural profession change in the face of the Pandemic?

Architecture is no longer the art of space-making solely. It is the art of housing nature. In this approach, architecture must consider all species as equal and address issues beyond human-centric needs and requirements. Architectural construction and building materials must be radically addressed, adding the ‘viral dimension’ to the virtual, pandemic-based architecture to parametric design. Microscopes and wet labs will become the new normal amidst computers, drafting boards, foam board models, and pencil sets. New legislation must be implemented banning the use of certain materials while expanding Neufert’s essential handbook to include anti-viral surfaces and viral modeling protocols. With computational growth and synthetic biology in the hands of designers, the built environment as we know it will forever change.

The pandemic is only the beginning of an inevitable end, a throbbing wake-up call for all things design. In a post-pandemic planet, architects are called upon to design complex systems rather than stand-alone products, self-regulating structures rather than distinctive buildings, ecological niches rather than human settlements. As we perpetuate the conditions for life on Earth, associations across scales, species, and domains will become germ-germane: soap and sabotage, SARS-CoV-2 and plastic containers, pandemic genocide and global warming, environmental pollution and biological evolution, the spread of a dubious living infectious agent and the phases of the moon. In the grand balance amongst the ancient learning of Pliny the Elder and the Social Network’s kaleidoscopic record of the inevitable, there is hope. The appearance of white swans and dolphins in Venice’s now clear canals is, after all, the best form of fake news we’ll ever tweet. The Gaia Hypothesis is not rocket science, nor it is a form of divine retribution. It is the proverbial philosophy that has given rise to the cradle of civilization: mother Nature, and she will mother you back.

Finally, what advice do you have for those starting their career in architecture? And in that, is there any advice you have specifically for women starting their careers in architecture?

The chances of a meteorite blitzing us into extinction are low compared with our demise due to climate change and related perils. I do unfortunately believe that the probability of anthropogenic human extinction within the next several hundred years (not thousands, not millions) is very real. Any of our current actions have direct impact on the future of our children in a very tangible way. Pandemics, global warming, nuclear annihilation, biological warfare and overall ecological collapse; one of those or their permutations will be—and is already—eliminating us from the precious planet we’ve brilliantly used and shamelessly abused. Ironically, we’re still in charge. And that’s where design comes in. If you’re thinking about a career in design, make it a calling; consider yourself drafted by Mother Nature. To engage with the built environment is no longer only about designing buildings and cities. It’s about designing systems that have the ability to impact our lives across every scale. As architects we need our own form of a Hippocratic oath. We need a range of harmonious activities to suit the species and enable continued biodiversity, to be universally applicable to architecture, urban design and to the design of all bio-mechanical things.