A Hybrid Model: Cousins Florencia Pita and Cecilia Quezada on Physical Impact and Collective Success

Florencia and Cecilia’s portrait by Kate Albee.

By Julia Gamolina

Florencia Pita is Principal of the LA-based design office Florencia Pita & Co., a creative platform dedicated to exploring architecture's multiple capacities, from the domestic environment to the urban landscape. The driving ideas behind Pita’s projects are based on her relentless use of color in architecture and the quest for novel, yet familiar forms.

Pita holds a licensure degree from the National University of Rosario in Argentina and an MA in Advanced Architectural Design from Columbia University, and has worked at Greg Lynn FORM, Gehry Partners, Eisenman Architects, and Asymptote. Her work was exhibited in the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, and is in the collections of MoMA, MAK Vienna, and Art Institute of Chicago, among others. She has taught at Yale, Princeton, and is currently faculty at SCI-Arc, alongside holding a visiting professorship at the University of Pennsylvania. Her monograph will be published in the Fall of 2021.

Cecilia Quezada is Principal and majority owner of Quezada Architecture, a San Francisco-based firm specializing in boutique lifestyle designs. A generalist, Cecilia brings a fresh design perspective to all projects as the lines between sectors blur and cultural paradigms continue to shift.

Cecilia received her Bachelor of Architecture and Certificate of Professional Practice from the University of Cincinnati, and has worked at Eisenman Architects and Studios Architecture. For over 25 years, Cecilia has compiled extensive local, national, and international experience in published and recognized planning and design commissions. Beyond architectural design, her project background encompasses sustainability, interior design, and master planning for commercial, hospitality, residential, civic, and mixed-use projects.

In their interview, Florencia and Cecilia talk about their shared history and how they came to collaborate, advising those just starting their careers to be intentional about mentorship.

JG: How did you grow up, and how did your interest in architecture first develop?

CQ: My mother, Ana Maria Guzman, was an Architect in Pittsburgh at the start of the 1970's. As an Argentine immigrant and mother during that time, her path was not an easy one. I was exposed to an architectural office at a very young age, coloring blueprints and overhearing her conversations. She definitely did not encourage me to follow her path, it was actually the opposite! I think she didn’t want me to have to struggle like she did to advance her career. Luckily, I was a defiant teenager and pursued architecture anyway and she was there supporting me every step of the way. I am so grateful that women like her paved the way for us.

FP: Alternatively to my cousin's upbringing in America, I was growing up in Argentina, a place with strong, thriving cultural communities. I was always told that architecture was related to math and science, but I always felt it connected more to the humanities, to art and literature. My mother was involved in literature and art, I saw the possibilities of design within an intrinsically human context.

When I was around eighteen years old, I had decided to formally pursue architecture. I was an exchange student for some time with Cecilia's family in the US, and built a relationship with her mother. Ana Maria was the one to introduce architecture to me as a built discipline, as she took me on a visit to Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater in Mill Run, Pennsylvania. It was like having a special tour guide into the history of architecture. I was hooked then, before ever even setting foot inside architecture school. Ornament, materiality, construction, the relationship to the landscape — these are all things I saw in Fallingwater and they are still relevant to my design ideas today. Ceci and I were lucky to be connected under her mentorship, and I can truly say it was a pivotal time.

CQ: It's funny you should say that...I took that for granted growing up, that she brought us to see important buildings and that architecture was part of our daily conversations — and I thought everyone's family was like that. Now my kids complain that Fred — my husband and also an architect — and I have to critique every building we see, so history repeats itself.

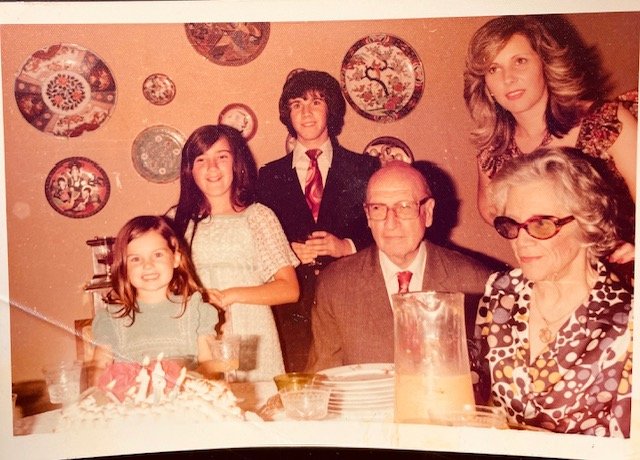

Florencia and Cecilia with their family in Argentina.

U.S. Pavilion at the 2016 Venice International Architecture Biennale, “The Architectural Imagination,” curated by Monica Ponce de Leon and Cynthia Davidson.

Eisenman Architects, 1999. Peter Eisenman and Florencia Pita.

What did you both learn about yourself in studying it?

FP: I remember Ceci's mom coming to visit me in undergrad in Argentina. I had shifted from a focus on materiality to one centered around color theory, studying the works of Luis Barragán, and I dissected it all with her. I was always trying to find referents in architecture, unique buildings that have challenged the discipline of architecture.

During my schooling in Argentina in the 90's, and then my Masters Degree in New York, I enjoyed being a student, taking in every aspect of the design discipline. In Argentina, the school of architecture trained you to see the discipline through the lens of modernism, as if time had stopped early in the 20th century, and I wanted to see beyond, and enter the 21th century. That is what I found at Columbia, I could see there the future of the discipline, with its focus on technology, and a theoretical framework that started to open up new paths of research. Much of what we teach today in architectural schools, have the foundations in the work done in the late nineties at Columbia University in NYC. I guess I could say that what formed me is that combination of past and future, of a shift from ‘building buildings’ to ‘building ideas.’

CQ: Through my education at University of Cincinnati, I learned that I enjoyed the more practical side of architecture as it was a six-year work-study program. I am grounded by the practicality of the built environment, and enjoyed my internships in offices the most. Both Florencia and I worked for Peter Eisenman a decade apart, but both were influenced by him in different ways.

How did you both get your start in the field?

FP: Peter Eisenman was the first office I worked in out of school in 1998. I spent a year in his office and developed a close, nurturing relationship with him and his wife, Cynthia Davidson. He wasn't building much at the time, so I was able to work on some of his amazing conceptual work. I was so young, and my year there launched me into my graduate education at Columbia University in New York with a sense of energy and excitement.

CQ: In 1988, I was an intern there for three months. I ended up working on theoretical projects which were a different typology for me. I considered his office another classroom, learning not just from Peter, but from his incredible team. The firm was full of strong thinkers; we would spend hours deep in theoretical discussions. To this day, it's one of the most unique office experiences I've ever had.

FP: Cecilia worked at Peter’s office in 1988 and I joined the office in 1998, and those ten years in between were transformational for the discipline at large, if you look at projects from the ’80s and those from the late 90’ you can see the shift towards the implementation of advanced software for design. To be more specific, during the 80’s the office designed and built highly relevant projects such as the Wexner Center for the Visual Arts and Fine Arts Library and the Carnegie-Mellon Research Institute, projects that rely on iteration and repetition, with clear diagrammatic processes, a kind of machine thinking with analog means, but in the 90’s unbuilt projects such as the Virtual House and the IFCCA Prize Competition for the Design of Cities -this last project where I had worked in the design team — these are projects that also focus on design processes and formal variations, but now they are aided by computation, and this makes their degree of variation exponential. This shift from analog design processes to design that is aided by the computer is what made architecture enter into the 21th Century.

I would say that today we are moving towards a hybrid model of design, one where the reliance and belief in computation is challenged, as we aim for things that have more character, more texture, more stories, less math and more myth.

“...we are moving towards a hybrid model of design, one where the reliance and belief in computation is challenged, as we aim for things that have more character, more texture, more stories, less math and more myth.”

How did the collaboration between the two of you come about?

CQ: We had always been looking for an opportunity to work together given our history. About twelve years ago, Quezada Architecture was working on various projects in Dubai that required a lot of innovative design. We invited Florencia to collaborate in our San Francisco office and got to work on a large masterplan and tower design together. That planted a seed.

FP: A few years ago, through a friend at Cumming, I had an opportunity to submit qualifications for a rebrand for UGG. I presented our teams collectively and won the project. Both Florencia Pita & Co. and Quezada Architecture bring their own strengths to form a complete set of skills for our clients at UGG. The brand reinvention and flagship store in New York City solidified our collaboration, seeing how well we worked together in sync. We each bring different perspectives and expertise to the table; Ceci's extensive knowledge in the field and all she has built throughout her career is a practical complement to my conceptual, comprehensive design approach. We merge the big picture with the built details.

Tell me more about the work you are doing together.

FP: We truly speak a similar language, besides our native Spanish [laughs].

CQ: The fact we are cousins, helps. We share a history and set of values, and when we see the results we are able to provide our clients, we know we're doing something right.

We're continuing to do work for UGG implementing the brand into new applications. Because of this partnership and the support of our client, QA has recently joined Florencia in her studio in the Arts District of Los Angeles to focus on growing a second office. We're so thankful to be joining forces with Florencia and continue to look for projects to collaborate on together.

UGG Logo form-making iterations.

UGG Store process, photography by Michal Czerwonka

UGG Store process, photography by Michal Czerwonka

Custom UGG Chair Design, photography by Michal Czerwonka

That’s incredibly exciting for you both! On that note, where are you in your career today? What does success mean to you both?

CQ: Along with my business partner, Julia Campbell, I am focused on building the business of QA, beyond great design. One of our firm's differentiators is being woman and minority-owned, and there aren't many firms like us who do the breadth of work that we do. While our core values stem from those distinctions, that's not necessarily what defines success for me. Our certifications afford QA opportunities to have real impact on the regions we practice, and that will determine the success of our legacy. These projects lead to partnering opportunities with other architects on highly visible, large projects that were otherwise unattainable, and therefore give our team the chance to learn about diverse project types in a variety of environments. As the future of the industry, their growth is our collective success.

FP: Currently my office is working on a monograph, and this has given us a chance to look at the work developed since 2006, the year of the first project I did independently. The monograph is like a lens that allows us to see everything and reflect on the work yet also question each project. In doing this book, we have revisited each drawing, each model, each photograph, and have filter them through categories to unwrap their conceptual logic and their aesthetic sensibilities.

Looking back at it all, what have been the biggest challenges? How did you manage through a disappointment or a perceived setback?

CQ: I had some challenging times pursuing my architectural degree in the late 1980's. There were only seven women in our graduating class of over 100 students. I had a male professor who relentlessly encouraged me and my female classmates to switch into interior design, to give up architecture. I would be lying if I said that didn't get under my skin.

My second year at university, I was hospitalized due to stress. This was my lowest point, and I considered giving up. At that moment, I had to decide if I wanted to quit, or push forward. I was terrified, seeing the effect that the stress was having on me, but I came to the realization that design was my passion and I couldn't live my life without seeing it through. This was a necessary wake up call, and I made a commitment to reevaluate how I manage stress and what I allowed to affect me.

Because I had missed class while at the hospital, I had to make up assignments over the holiday break. My professor asked if I had someone at home, implying my father, to help me with my work. When I told him my mother was an accomplished architect, he was stunned. I felt so proud in that moment. I felt defiant in the face of all the doubt of my existence in that program. I had to prove everyone wrong and finish.

“I came to the realization that design was my passion and I couldn’t live my life without seeing it through. This was a necessary wake up call, and I made a commitment to reevaluate how I manage stress and what I allowed to affect me.”

Who are you admiring right now and why?

CQ: Having just completed a project with Studio Gang at Mission Rock in San Francisco, Jeanie Gang comes to mind. It's impressive to see what she's built with her studio, not just design-wise, but also the business behind it. I'm also inspired by Neri Oxman. She is taking architecture to new, inspiring realms as the leader of the Mediated Matter research group at MIT Media Lab. She is reviving architecture as a multidisciplinary field, incorporating biology and focusing on materiality and space. I admire them both for pushing the limits of architecture.

FP: I am inspired by the community of women that have supported me throughout my career: architects, friends, and colleagues. The cultural shift of our modern times is palpable. Women are in charge of their domains, and that drives me forward.

An amazing community of women from Monica Ponce de Leon at Princeton, to Winka Dubbledam at UPenn, Cynthia Davidson editor of Log, Deborah Berke at Yale, Sylvia Lavin at Princeton, my cousin Cecilia and all my fellow colleagues at SCI-Arc such as Jackilin Hah Bloom, Marcelyn Gow, Elena Manferdini, and many more . These women invited me to teach at different places, host exhibitions, and allowed me to expand my knowledge and impact future generations. These women have been in my corner since the beginning and I wouldn't be where I am without them lifting me up.

UGG Flagship Store, 5th Avenue NYC, photography by Amy Barkow

UGG Flagship Store, 5th Avenue NYC, photography by Amy Barkow

UGG Flagship Store, 5th Avenue NYC, photography by Amy Barkow

What is the impact you’d like to have in/on the world? What is your core mission?

CQ: The reality is that we are working in the built environment so our impact is physical. I hope we leave the world with better architecture! I want to create places that are beautiful, sustainable, fun, and allow people to thrive.

FP: Representation is so important. We are making a path for not only the next generation, but also our current peers. As a professor, I see students start from the very beginning and transition to the real world. There is a gap from academia to professional practice, and my goal is to see more women confidently enter the design industry and know there is a place for them.

At my core is the belief that design can make a difference. The impact is in how people live, and the quality of their lives. We are finding solutions to real problems, for example a current project of ours: designing a small town as a retreat for homeless moms, we are partnering with the non-profit entity title Tiny Town and currently we are in the early steps of this process trying to help them envision their ideas and also embark in the process of fundraising, so we can make sure to build this place, as it will make a huge impact in the life of many woman and their children. I do believe in the power of design, architects are trained to think differently, to find myriad alternatives to complex problems, so if we can bring our design thinking to projects with social impact, because social impact is also human impact. .

CQ: We seek out projects that will make our communities better. We can't solve every problem, but we can tackle one project at a time to make a difference on an individual scale.

Finally, what advice do you have for those starting their career?

CQ: Seek out mentors and mentees. Everyone you come across is a teacher, whether it's in school, or your job, or while travelling the world. Be a sponge! Be confident in your abilities no matter where you're at, because architecture is a long pursuit. I love that I still learn something new every day.

FP: I agree with Cecilia: mentorship is key, and it's true for everybody. I'm a professor by title, but you can find mentors everywhere. Find guidance through human connection, and let that be your driving force.

In the past, we may have given women different advice, but we are fortunate to be in the United States today, in 2021. We're shifting that narrative. Other places in the world don't have that privilege, and so we must also strive to build equity everywhere.