I Am An Artist: An Essay on an Architect's Identity

NCJ Self-Portrait

By Nina Cooke John

What should we call you?

“What should we call you? Artist? sculptor…?” I hadn't ever considered either of those titles for myself. I am an architect. I had used the title since 2000 when I passed the last of my nine ARE exams. I had added professor, wife, mother, and even urbanist, but not artist. Why not?

Once I got on the science track in high school, I had to drop art to pick up physics and chemistry. I didn't pick art back up again until my last year of high school when I started taking evening painting and ceramics classes. Many of my colleagues in architecture school were really artists at heart whose parents had convinced them that architecture was a more reasonable option. Working class, immigrant, and African American parents saw no secure future in an art education. During a lecture at the School of the Art institute of Chicago the Jamaican artist Ebony Patterson described how her father asked why she needed to go to art school when she could already draw. These friends of mine had been engrossed in the art world throughout high school and were now doing their best to reign in their inner artist as they learned about form, space, and order. That wasn't me though. I was a science girl just learning how to tap into her creative side. I was just beginning a new relationship with my intuition. Architecture school helped me to marry creative expression with problem solving. But is that art?

Nina Cooke John, "Point of Action" Flatiron Plaza, NYC. photo credit Tony Turner Photography

Where does art end and architecture begin?

Studio art electives are typically a part of the comprehensive curriculum of architecture schools. When I arrived in New York and started studying architecture, I basked in the freedom I found in my painting class working with charcoal and making blind contour line drawings that forced me to keep my eyes on the model and not look down. I was, at the same time, basking in the freedom of being away from home and finding myself in a city that was arguably at the center of the art world. I immersed myself in the canvas of the city, with its diverse faces, architectural styles and cacophony of languages. It was also the first time that I was let loose in a museum to wander around as I pleased. In 1989, MoMA had a much smaller footprint and had a fraction of its current visitorship. I could, and I did, spend hours just hanging out in the galleries. But the city was its own gallery. Art on the sidewalks, walls, signs, and on the bodies of the people. I was soaking up the intensity of the city through the lens of an architecture student, while making art a part of my life.

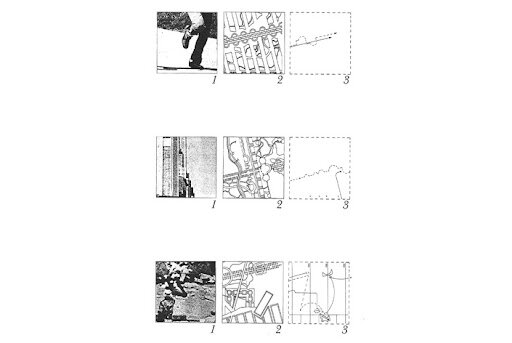

We had drawing classes specifically for architects. Classes that teach us how to create orthogonal projections and to creatively express our design concepts and processes. Except for that one teacher at Cornell that had us draw to music, putting lines on paper based on our emotional responses, my experience with architectural representation drawings is that they are not as expressive as charcoal. They have a specific function. And maybe that is where art ends and architecture begins. Though our drawings can be seen as works of art, as architects we design in service of others. We address problems that relate to how people will occupy space as part of their everyday lives. The lines on paper will come alive and the physical space must respond to the concrete needs of those for whom it is built. Yes, architecture on paper is still architecture. But even conceptual architecture that explores the intricacies of form on paper is put to best use when those conceptual explorations are, ultimately, addressing real world ways of engaging with each other in space. (In architecture school I was obsessed with Bernard Tschumi’s Manhattan Transcript drawings for their experimentation with photography and movement notation to depict how events activate a space. Tschumi’s website describes them as “…neither real projects nor mere fantasies”[1]. I believe they lead directly to the success of the follies at Parc de La Villette, a park “based on culture rather than nature”[2].) Artful drawings and practice lead to a rich architectural embodiment. But art and architecture are not the same. Architecture cannot only be in service of the lines on the paper. Art, conversely, is allowed the privilege of being purely expressive. Art for art’s sake.

Bernard Tschumi, "Manhattan Transcripts" photo courtesy Tschumi.com

So much of our engagement with art is lost in the day-to-day practice of architecture. My days are filled with navigating client relationships, managing contractors and the smooth running of the office. The liberating practice of incorporating artistic explorations in our design process is often eliminated for the running of a more efficient office.

There is much that we can take from art in the service of architecture and not only in formal expression. Lesson one: Learn to look (and listen). One of the first things that they teach in an amateur drawing class is the art of looking. That is, how to be observant. To create a realistic rendition, one must look closely at what is there. You must drop any pre-formed ideas about a subject and just see. Lesson two: Context is important. A realistic rendition will include the contours within and without the figure; the white space on the page and how all the parts work together are important to the composition. I painted my first (and only) self-portrait in a class at Cornell. I stood in front of a mirror in the studio for many hours forcing myself to just see the lines, colors and textures that were there and not bring to the drawing the many worries of how I thought I looked. This is a difficult task for a young woman who didn’t often see herself represented in the world. I had to see not what I imagined others saw, but what was there. Lesson three: Spend the time needed to just look. “A Guide to Slow Looking” on the Tate Modern’s website describes a process of looking at art not for the artist but for the museum visitor. “…what happens when we spend five minutes, fifteen minutes, an hour or an afternoon really looking in detail at an artwork? This is 'slow looking'. It is an approach based on the idea that, if we really want to get to know a work of art, we need to spend time with it…Try to forget any expectations, as well as anything you 'know' about the artwork…See things from a fresh perspective. Make the familiar strange. Try and spot the details hiding in plain view.”[3] If we really want to get to know a place or community for whom we are creating space, as architects we need to spend time with it, with the place and with the people.

Jean Claude and Christo "The Gates" photo credit Art Anderson via Wikimedia Commons

Art and the City

Cities are complex places. “Nearly 70% of the country’s largest cities are more racially and ethnically diverse than they were in 2010”[4] and cities are home to half of the world’s population and provide three-quarters of its economic output.[5] We know that artists are drawn to cities, they are also drawn to the mountains and to the desert, but there is something about the vibrancy, access to a creative community and the inherent diversity that make metropolitan cities hubs for art and artists. They ground the creative culture and are also instrumental in social commentary on life in the city and on the forces of marginalization.

Ai Wei Wei’s 2017 “Good Fences Make Good Neighbors” installations across the 5 boroughs of the city included large pieces that claimed space in iconic parks and landmarks, as well as small installations that would be easy to miss if you weren’t paying attention. You walked under some, stood beside some, looked up at some and lied down and looked up at the sky from some. Some you might only notice at night. They were deployed such that they were integrated into the environment across the boroughs, people engaging with them every day. As a collection, they were a powerful commentary on migration, borders, and the division of people.

My first experience of a large-scale installation was Jean-Claude and Christo’s The Gates in central park. That piece produced in me a connection to Central Park that I hadn’t ever experienced before. The color, structure and textures of the installation were so foreign to the landscape of the park, yet, as they followed the pathways up and down the hills, they integrated seamlessly. As I was transfixed by the fabric moving with the wind, the trees of the park and even the buildings beyond were brought into clearer focus as the installation forced me to notice what had before faded into the background. Public art’s power is its ability to stop us in our tracks, pull us out of the distractions of our everyday routines, and force us to look at our environments in a new way. By slowing down, we connect with our city and the people in it in ways that we hadn’t before.

Ai Weiwei "Good Fences Make Good Neighbors" Washington Square Park. photo credit" John P St. John via Flickr Commons

I am an Artist

art·ist | \ ˈär-tist

1a: a person who creates art (such as painting, sculpture, music, or writing) using conscious skill and creative imagination. Source: Miriam Webster Online

I am an artist. My practice has expanded to include public art and I am creating more art through collage, painting and drawing. The work definitely informs the work I do as an architect and urbanist. I had always been interested in how publicly engaged architecture promotes placemaking – creating community beyond the confines of private space. I am interested, though, not only in how the spaces we create promote public recreation but also the role that public art plays in promoting political action. We saw the art that popped up on the protective plywood during the Black Lives Matter protests. We also saw the collective artwork of Black Lives Matter street murals across the country. Those are good examples of artists lending their talents to a movement and enhancing its impact through their efforts. What I am most interested in, however, is how – because of the art that we put in public spaces, the same artwork that might promote dancing and singing and performance around them – how these, through daily, sustained encounter, might encourage everyday citizens to organize.

[1] http://www.tschumi.com/projects/18/

[2] ibid

[3] “A Guide to Slow Looking”. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/guide-slow-looking

[4] https://www.usnews.com/news/cities/articles/2020-01-22/americas-cities-are-becoming-more-diverse-new-analysis-shows

[5] “Turning to the Flip Side”, Maruxa Cariama Just City Essays